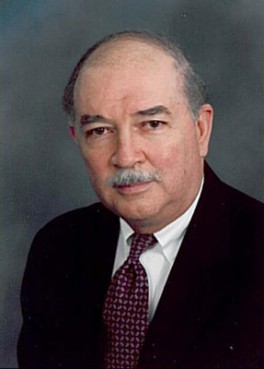

(RNS2-AUG04) Dominic Aquila is the chief justice of the Standing Judicial Commission of the Presbyterian Church in America, which ruled that a church member could be removed from church roles because of his racist views. For use with RNS-CHURCH-RACE, transmitted Aug. 4, 2010. RNS photo courtesy PCA.

(RNS) It started with an e-mail message the Rev. Craig Bulkeley decided he simply couldn’t let pass.

To the pastor in Black Mountain, N.C., the e-mailed comments from controversial church member Neill Payne — about the inability of black Africans to lead Zimbabwe — amounted to racism, pure and simple.

Then he got to the postscript.

“PS:,” the e-mail said. “IQ is the best and most reliable and most accurate predictor of these results.”

Whether the message was a display of racism or a matter of misinterpretation is a question that roiled the predominantly white Presbyterian Church in America for close to three years. The steepled brick church nestled in the Blue Ridge Mountains east of Asheville nearly split over the fallout, and Bulkeley nearly lost his job.

The debate moved members of the conservative denomination from lofty statements about racial reconciliation to a real-life congregational feud that eventually drew the attention of hate-group watchdogs at the Southern Poverty Law Center.

Arguments over Payne’s fate reached the denomination’s supreme court, which confirmed that Payne’s removal as a “ruling elder” was appropriate.

“We’re saying if you’re going to be an officer of the church and hold these views, this is out of accord,” said Dominic Aquila, a seminary president who served as the chief justice of the three-judge panel that heard Payne’s case.

After lingering debates, and at Payne’s request, the soft-spoken chiropractor was removed from the roll of some 50 members at Friendship Presbyterian Church in May.

Payne remains insistent that his e-mail was misunderstood, and though Bulkeley never anticipated the long process that led to Payne’s removal, the pastor said the battle was worth fighting.

“To me, it was just the right thing to do,” he said.

The church court decision came five years after the PCA issued a pastoral letter on racism. “For years,” the statement said, “we have left unattended in our midst the vestiges of racism, and the reality of its raw presence within corners of our denomination.”

Experts beyond the 346,000-member denomination say it is unique — even remarkable — for a PCA church to have gone so far to stamp out racism.

“For a PCA minister to do that, that’s rather unprecedented,” said Dennis Dickerson, a history professor and expert on African-American religious history at Vanderbilt University.

At one point in the legal wrangling, Payne signed a confession statement. “I have failed to hold my views concerning race in a way that disassociates them from the opprobrium and odium that attach to such views in other contexts,” it said.

Aquila’s Standing Judicial Commission last year left it up to the local Western Carolina Presbytery to determine whether to put Payne on trial to further investigate “the biblical character” of his views.

When Payne asked to be removed from the Black Mountain congregation, he and the church were spared a formal trial. Yet the damage was already done.

Robert Woodward, another former member of Friendship Presbyterian Church, said Bulkeley’s charges against Payne alienated “over half the congregation.”

“I just felt like Neill’s opinions was not something addressed specifically in the Scriptures and therefore he had a right to hold them,” he said.

(BEGIN FIRST OPTIONAL TRIM)

Joel Belz, a former PCA moderator and ruling elder within the Western Carolina Presbytery, was one of the people who challenged Payne’s views.

“We believe as a matter of his theological sanctification before a holy God he did not have the right to be immersing himself … in the probability of IQS based on `The Bell Curve,”‘ said Belz, referring to the controversial 1994 book that linked African-Americans and lower IQ scores.

(END FIRST OPTIONAL TRIM)

Several leaders say the Black Mountain case marked the first time any Presbyterian denomination has disciplined a member over the issue of race — a turning point beyond a past that is at least colored with racism.

The Rev. Joel Alvis, author of “Religion and Race: Southern Presbyterians, 1946-1983,” said disputes over supporting racial equality were among the “constellation of issues” that led to the creation of the PCA in the 1970s.

“I don’t think you could say it was the defining element, but it certainly was a strand as it was a strand in Southern cultural life,” said Alvis, an interim pastor in the larger and more liberal Presbyterian Church (USA).

(BEGIN SECOND OPTIONAL TRIM)

PCA archivist Wayne Sparkman said there were “undoubtedly” racists among the PCA’s first members, but its founders also included men “who were not motivated by any shade of racism and wanted to have a denomination that was above that.”

(END SECOND OPTIONAL TRIM)

Payne says conclusions that his case marked a turning point in PCA racial history are “poppycock.” He stands by his remarks in the original e-mail message, but disagrees with how they have been characterized.

“It gets very difficult to know what is racist and what isn’t because the goalpost keeps changing every day,” he said. “I’m not a racist. … The postscript that Mr. Bulkeley made such a big deal about was just an offhand comment that my friends would have known was not meant to demean or to say anything untoward.”

He defends the bottom line of his message: “When people are tested with IQ, … the results break down by race, with the Orientals being on top, the Caucasians next, Hispanics after that and then blacks, and that is consistent over many years.”

Payne also acknowledged that he was married in 1990 on the grounds of the Church of Jesus Christ Christian, which was run by leaders of the Aryan Nations, a white supremacist group.

Bulkeley said his response to Payne’s e-mail message, and the resulting legal battle, reflected a desire to clarify his congregation’s stance.

“The church had something of a reputation among some people of being, if not a white supremacist church, at least sympathetic to white supremacist ideas,” he said. “My hope from early on was that this dispute would lead to the clearing up of the reputation of the church, and to Neill Payne assisting in clearing up that reputation and his own.”