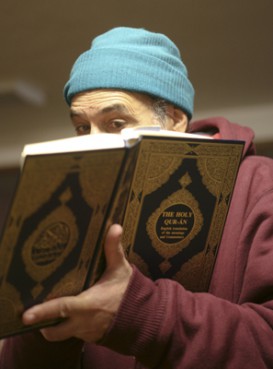

(RNS1-NOV29) Mohammed Moussaoui reads a passage from the Quran for a visitor at the Salman Alfarisi Islamic Center in Corvallis after a suspected arson broke out at the mosque when an OSU Muslim student was charged with plotting to detonate a bomb at the Christmas tree lighting ceremony in Portland. For use with RNS-MOSQUE-ARSON, transmitted Nov. 29, 2010. RNS photo by Ross William Hamilton/The Oregonian.

(RNS1-NOV29) Mohammed Moussaoui reads a passage from the Quran for a visitor at the Salman Alfarisi Islamic Center in Corvallis after a suspected arson broke out at the mosque when an OSU Muslim student was charged with plotting to detonate a bomb at the Christmas tree lighting ceremony in Portland. For use with RNS-MOSQUE-ARSON, transmitted Nov. 29, 2010. RNS photo by Ross William Hamilton/The Oregonian.

CORVALLIS, Ore. (RNS) The damage from a fire at the Salman Alfarisi Islamic Center early Sunday (Nov. 28) did not amount to much in material loss. But the symbolic wound went far deeper.

Fire was apparently set to the mosque just a day after one of its on-again, off-again members was arrested in connection with the attempted bombing of the annual Christmas tree lighting in Portland’s Pioneer Courthouse Square.

Hours after the fire, the charred pages of Islam’s holy book, the Quran, sat side by side with a burned chair, computer and the rest of the charred detritus.

Art Balizan, the FBI special agent in charge in Oregon, and U.S. Attorney Dwight Holton visited the scene of the fire and delivered a message of support and tolerance to the Islamic center’s leaders and members.

“Religious freedom is one of the pillars of American society,” Holton said.

Balizan said there was unspecified evidence of arson, but declined several chances to directly link the arson with Friday night’s arrest of 19-year-old Mohamed Osman Mohamud, a Somali-born student at nearby Oregon State University.

According to federal officials, Mohamud allegedly pressed the buttons on a cell phone he thought would trigger a “spectacular show” in downtown Portland, the two-year anniversary of the terrorist attacks in Mumbai, India that killed 166 people.

The government’s criminal complaint against Mohamud doesn’t say precisely when the FBI first took notice of the naturalized U.S. citizen born in Mogadishu, Somalia, in January 1991. But the bureau began to intercept his e-mails about violent jihad in 2009.

Mohamud is accused of the federal crime of attempted use of a weapon of mass destruction. If convicted, he faces a maximum sentence of life in prison, according to the U.S. Department of Justice.

A day before Sunday’s fire, leaders of the mosque that Mohamud sometimes attended had released a statement condemning the alleged bomb plot.

“We denounce this horrible plot in the strongest terms and repudiate all those who commit such acts of mindless violence in the name of Islam,” the statement said. “Islam is a religion of peace and these acts are not the legitimate acts of Muslims.”

The fire was reported at 2:15 a.m. on Sunday morning and burned 80 percent of the center’s office before firefighters extinguished it. No one was injured.

The center’s statement had urged the public to keep from assuming that Mohamud’s alleged actions represent the Somali or Muslim communities as a whole. Imam Yosof Wanly said he doesn’t believe the fire is a reflection on the local community, where he has lived for 24 years.

“I know people here know the true reality of the Muslim community here,” Wanly said. “It’s a sad situation.”

Standing outside his brother’s Hashi Halal Market in North Portland, Ahmed Ali said the only thing he wants is for the world to know that Somalis are nothing like their countryman who’s charged in the attacks.

“He ruined it for everybody,” said Ali, 24. “We are against it. Our religion says we cannot kill innocent people. This is the reason we left Somalia.”

Mosque officials said Mohamud had visited only once or twice a month since he arrived at OSU in fall 2009. He withdrew from classes on Oct. 6, according to federal officials.

Eesaa Moussaoui, a 22-year-old engineering student at OSU, described the suspect as “friendly, very jovial, really outgoing. He said Mohamud smoked tobacco and drank alcohol while he was in Corvallis, which are both forbidden for devout Muslims.

Amina Vora, 19, a Muslim exchange student from London studying history, met Mohamud on Nov. 23 at a social event sponsored by the African Student Association. “He didn’t seem that religious or even moderately religious to me,” said Vora.

Government officials allege that Mohamud was angry at his parents for keeping him from jihad and had thought about carrying out an operation since he was 17.

“To my parents, who held me back from Jihad in the cause of Allah. I say to them, if you make allies with the enemy, then Allah’s power will ask you about that on the day of judgment …,” Mohamud said in a video he recorded before the aborted bombing, according to court documents.

Friends and neighbors said they did not recognize the would-be terrorist described in court documents.

“He was a good kid who made good grades,” said Stephanie Napier, who lived across the street from Mohamud’s parents in Beaverton. She and her husband described Mohamud as an intelligent, polite, quiet teen who graduated early from high school and moved to Corvallis for college.

The Napiers said Mohamud’s family moved away sometime in the summer of 2009, around the time that the parents, Mariam Barre and Osman Barre, split up. “He was a quiet kid, but with his folks splitting up, who knows,” Adam Napier said.

(OPTIONAL TRIM FOLLOWS)

Brandon Guffey, 20, who played basketball with Mohamud in middle school, said neither Mohamud nor his Muslim friends were known as particularly religious.

“That’s what the biggest surprise was. It was totally out of the blue. They never tried to argue with anyone about it. They were never actively touting it. They were just people.”

Local Muslims leaders tried to downplay as “inconsequential” the threats they had received following Mohamud’s arrest, saying the incident need not affect sometimes-strained relations between Muslims and non-Muslims.

“Tensions are what you make of them,” said Shahriar Ahmed of Beaverton’s Bilal Mosque Association. “There is no point in increasing tension. There is no point in flaring things beyond what they need to be.”

(Allan Brettman writes for The Oregonian. Molly Hottle, Kelly House, Candice Ruud, Lynne Terry, Brent Hunsberger and Bryan Denson of The Oregonian staff contributed to this story.)