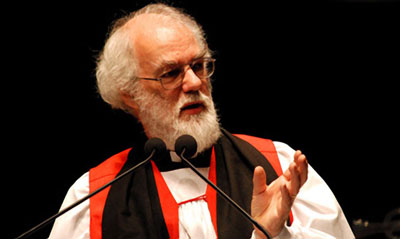

(RNS6-SEPT26) Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams is spiritual leader of the Anglican Communion. Religion News Service file photo.

CANTERBURY, England (RNS) Nearly a millennium ago, four unruly knights crossed the English Channel from France and confronted the archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Becket, over his feud with King Henry II.

Before the knights smashed the future saint’s skull in front of monks at an altar inside Canterbury Cathedral, Henry is said to have wondered aloud, “Who shall rid me of this turbulent priest?”

These days, Prime Minister David Cameron might be wondering the same about the current archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams.

Williams sparked a political row by criticizing the government’s austerity measures and budget cuts as the cause of “bafflement and indignation,” saying they are nothing more than “radical, long-term policies for which no one voted.”

To be sure, Williams’ two most recent predecessors angered the governments of their day when Robert Runcie confronted Margaret Thatcher over budget cuts in the 1980s and George Carey blasted Britain’s support for the war in Iraq.

But never have the words of a sitting archbishop of Canterbury caused quite so much anger as Williams’ during his stint as guest editor of the left-leaning New Statesman magazine earlier this month.

The very public flap threw a spotlight on Williams’ twin roles as head of the Church of England and also the 77 million-member worldwide Anglican Communion, and the difficulty of doing both.

If he wades into national politics, critics say he should instead return to ensuring his global flock doesn’t break up over human sexuality. Yet if he ignores the politics of the day, he’s criticized for not using his bully pulpit.

Less than two months after the media hailed him as a “national treasure” when he officiated at the wedding of Prince William and Kate Middleton, Williams has become, in the words of the Sunday Times’ Minette Marrin, a “wordy, holy, hairy man” who is “hustling his tiny flock towards the cliffs of disestablishment with the foolish, self-destructive recklessness of Don Quixote.”

Former Times editor William Rees-Mogg was a tad more succinct in blasting Williams’ critique of government spending cuts. Williams, he said, had shown a distinct lack of “Christian charity.”

Writing in the New Statesman’s June 9 issue, Williams questioned the value of the coalition government’s reforms, and charged that Cameron’s “Big Society” platform had been conceived for “opportunistic and money-saving reasons” and that its ideas were “painfully stale.”

Taken aback by Williams’ public critique, Cameron rejected Williams’ views but nonetheless said he had every right to express them. For good measure, Britain’s top Roman Catholic prelate, Archbishop Vincent Nichols, sided with Cameron.

Williams has received support from some quarters of the church, including a handful of bishops and one retired priest, the Rev. John Papworth, who said, “Not only does the Archbishop of Canterbury have a right to engage in public debate, but it is also his duty.”

Others in the Church of England have noted this is not the first time Williams stepped into the political arena.

He has condemned racism and advised voters not to support the far right-wing British National Party (BNP). In 1985, Williams was arrested during a protest organized by the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament at a U.S. air base in Suffolk.

Williams comes from a tradition of activism in a poor part of Wales, and was born into a family of Presbyterians-turned-Anglicans who were steeped in a strain of Anglo-Catholicism.

By criticizing the current coalition government, Williams opened himself up to questions about his own leadership skills, both in the Church of England and the larger communion, where he has the power of persuasion, but little else.

Within the Anglican Communion, conservative Third World archbishops have blasted him — and subsequently gone on to mostly ignore him — for not disciplining the independent-minded U.S. Episcopalians and Canadian Anglicans for their embrace of homosexuality.

Western liberals, meanwhile, likewise ignored his pleas not to ordain openly gay bishops or bless same-sex unions, and rebuffed his plans for an Anglican “covenant” that would bind the communion’s 44 member churches.

Williams, 61, has said that he would love to spend less time talking about homosexuality in order to concentrate on what he calls “the real issues” — hunger, poverty and disease, especially in the developing world.

Yet when he does, as in the New Statesman article, conservative critics say he should spend more time healing the bruised Church of England and leave politics to the politicians.

Marrin, from the Sunday Times, said the incident reflected the church’s unique role in governance of the state, and vice versa — and not in a good way.

“It has long been clearly absurd that a priest without any mandate from anyone, other than a few quarrelsome men in frocks, should have any ex officio position of power,” she wrote. “Yet the Archbishop of Canterbury sits in the House of Lords and so do 25 other Anglican lords spiritual by right of unelected office.”

An editorial in The Daily Mail suggested that if Williams wants to make political speeches, “he should resign and join the Labor Party which over the last 13 years did such harm to the fabric of British society.”