CHARLOTTE, N.C. (RNS) On the night the Democrats became the first major U.S. political party to endorse gay marriage, some convention delegates remembered how it used to be — back in high school, back in the closet, back in the days when, as one said, “you’re scared because it’s not OK to be who you are.”

Michelle Obama speaks during the Democratic National Convention in Charlotte, N.C. on Tuesday night (Sept. 4, 2012).

Heather Mizeur, once a student at Blue Mound (Ill.) High, now a Maryland legislator and one of more than 500 gay delegates to the Democratic convention, said the vote Tuesday (Sept. 4) approving the platform’s marriage equality plank was “one of those historic moments. It says our relationships should be treated equally.”

It also marked a turnaround from three months ago. After North Carolina voters approved a state constitutional referendum in May limiting marriage and domestic unions to heterosexuals, some Democrats called for the convention to be moved out of the state.

The organization Gay Marriage USA said nearly 20,000 people signed an online “move the convention” petition.

Even in North Carolina, “a lot of people were saying (to convention officials), ‘You all shouldn’t even come here,'” recalled Lindsey Simerly of the Campaign for Southern Equality, a civil rights group based in Asheville. “We were all a little mad and discouraged.”

A month before the vote, while she was here for a meeting of the Democratic National Committee, Mizeur said gay and other convention delegates might “keep our money in our pockets” rather than reward the state for approving a “mean-spirited” amendment.

But after President Obama announced his support for legalizing gay marriage — one day after the North Carolina vote — “the air changed,” said O’Neale Atkinson, operations manager of the LGBT Community Center of Charlotte. “When you’re looking at the hope of federal change, that state vote is easier to take.”

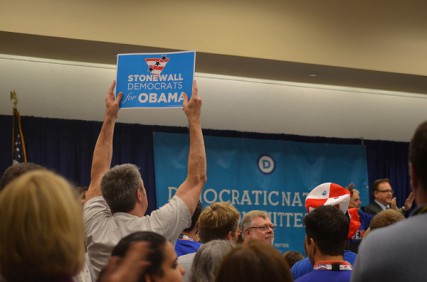

Attendees clap during the LGBT caucus of the 2012 Democratic National Convention in Charlotte, N.C. on Tuesday Sept. 4, 2012.

By Tuesday, most members of the Democratic Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Caucus had come to regard Charlotte as a positively congenial locale to celebrate their victory and spread their message.

“I was at a party Sunday night and it was jammed,” said Janice Covington, 65, North Carolina’s first transgender convention delegate. “There was a lot of energy, a lot of people making contacts. We have to reverse this (amendment), and that means talking to people who don’t know who we are.”

The platform approval could have been less momentous. Earlier this year, Mizeur said, its wording on gay marriage was the subject of “a lot of wrangling.” That changed after Obama endorsed legalization. Then, she said, “very strong marriage equality language” became inevitable.

The platform supports overturning the 1996 Defense of Marriage Act— signed by Wednesday night’s keynote speaker, former President Bill Clinton.

Long before the platform vote, “everyone knew it was going to happen,” acknowledged Ryan Butler, 33, a North Carolina delegate. “But to actually be here and to be a part of it … I will remember this for the rest of my life.”

The platform provision was expected to ratchet up the political battle over gay marriage; several other states face constitutional referendums. And in North Carolina, the National Organization for Marriage,which opposes gay marriage, has been airing radio ads aimed at religious African-Americans.

A man holds up a signs that reads ‘Stonewall Democrats for Obama’ during the LGBT caucus of the 2012 Democratic National Convention in Charlotte, N.C. on Tuesday Sept. 4, 2012.

The group’s president, Brian Brown, says Obama’s support for gay marriage ensures he’ll be a one-term president. And Brown says Obama will lose North Carolina, where Democrats helped the constitutional amendment pass with 61% of the vote.

Democrats have grappled with gay rights language for decades. At the 1972 convention in Miami Beach — when gay delegates “could have fit in a phone booth,” recalled Rick Stafford, a Minnesotan who was there, and who now chairs the LGBT Caucus — a coalition of gay rights groups drew up a proposed platform provision that called for repealing laws against homosexuals marrying. After the party platform committee rejected the coalition report by a vote of 54 to 34, two delegates —Jim Foster and Madeline Davis — spoke on its behalf from the podium.

University of Massachusetts historian Julio Capo says it was the first time homosexual rights were advocated before TV cameras at a national convention.

Foster died of AIDS in 1990.

Davis, now 72, watched the convention on TV at home in Buffalo, N.Y., on Tuesday. “We asked for this 40 years ago, and it’s taken this long for this to happen,” she said. “It’s not yet the law of the land, but it’s a major step forward.”

(Rick Hampson writes for USA Today.)