(RNS) At its heartwarming core, Christmas is the story of a birth: the tender relationship between a new mother and her newborn child.

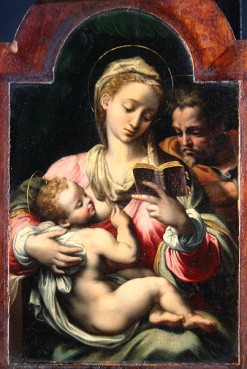

Indeed, that maternal bond between the Virgin Mary and the baby Jesus has resonated so deeply across the centuries that depicting the blessed intimacy of the first Noel has become an integral part of the Christmas industry.

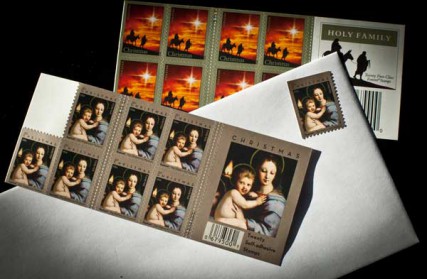

Yet all the familiar scenes associated with the holy family today – creches and church pageants, postage stamps and holiday cards – are also missing an obvious element of the mother-child connection that modern Christians are apparently happy to do without: a breast-feeding infant.

Jesus certainly wasn’t a bottle baby. So what happened to Mary’s breasts? It’s a centuries-old story, but one that has a relatively brief answer: namely, the rise of the printing press in 15th-century Europe.

With the advent of movable type, historians say, came the ability to mass-market pornography, which promoted the sexualization of women’s bodies in the popular imagination. What’s more, the printing press enabled the wider circulation of anatomical drawings for medical purposes, which in turn contributed to the demystification of the body. Both undermined traditional views of the body as a reflection of the divine.

Workshop of Sandro Botticelli (Italian). ‘Madonna and Child with the Young Saint John the Baptist,’ 1495-1499. tempera and oil on wood panel. Walters Art Museum (37.422): Acquired by Henry Walters with the Massarenti Collection, 1902. **Note: this image is not available to download.

The other major consequence of this new technology, of course, was the mass-marketing of the Bible and the rise of a Protestantism that encouraged a focus on the text of the Scriptures and discouraged the use of images and “Catholic” practices like devotion to the Virgin Mary and the saints.

The cultural shift was so great that even Catholics soon came to regard the breast as an “inappropriate” image for churches. Instead, the sacrifice of the cross – the suffering Jesus – became the dominant motif of Christianity while the Nativity was sanitized into a Hallmark card.

“Ask anybody in the street what’s the primary Christian symbol and they would say the crucifixion,” said Margaret Miles, author of “A Complex Delight: The Secularization of the Breast, 1350-1750,” a book that traces the disappearance of the image of the breast-feeding Mary after the Renaissance.

“It was the takeover of the crucifixion as the major symbol of God’s love for humanity” that supplanted the breast-feeding icon, she said. And that was a decisive shift from the earliest days of Christianity when “the virgin’s nursing breast, the lactating virgin, was the primary symbol of God’s love for humanity.”

In fact, the oldest known image of the Virgin Mary is from a third-century fresco in a Roman catacomb that shows the infant Jesus suckling at her exposed breast.

From those early traces, the motif of “Maria Lactans,” as it is called in Latin, became increasingly popular – and increasingly graphic – an illustration of what the Catholic writer Sandra Miesel called “the shocking fleshiness of our faith.”

By the Middle Ages, the breast-feeding Mary was shown in every possible context, and “lactation miracles” and “milk shrines” proliferated across the Christian world. Mary was “the wet-nurse of salvation,” as one phrase had it, offering holy succor to communities exposed to the vagaries of war and disease. Some images of St. Bernard of Clairvaux even show him kneeling in prayer before a statue of Mary, who is squirting breast milk onto his eager lips.

Lactatio (milk wonder) of Bernhard of Clairvaux “Bernard receiving milk from the breast of the Virgin Mary. The scene is a legend which allegedly took place at Speyer Cathedral in 1146.” **Note: This image is not available to download.

It was all deeply moving to believers of the day, though perhaps too much of a good thing even then. Miesel says that a century before the Reformation, St. Bernardine of Siena quipped that “Mary must have given more milk than a hundred cows.”

Yet once the breast became an object of medical and sexual interest, it quickly vanished as an object of sacred desire.

Miles said she found no religious paintings of a breast-feeding Mary after 1750, even as exposed breasts became a common feature of classical, non-Christian paintings, like “Liberty Leading the People,” which commemorates the French Revolution, or the Roman woman Cimon breast-feeding her starving father.

So after all this secularization and sexualization can the breast make a comeback as a religious symbol?

The potential is there. Some conservatives are pushing the nursing Jesus as a symbol for the anti-abortion movement, while believers of a more liberal bent have cited the breast-feeding Virgin Mary as an inspiration for social justice policies. And many Latino Catholics have preserved a devotion to La Virgen de la Leche, a following that could grow along with the influx of Latinos to the U.S.

Still, it’s hard to imagine Christmas cards of a baby Jesus at Mary’s breast arriving in mailboxes anytime soon.

Even as the number of breast-feeding mothers continues to grow, public breast-feeding is still a source of provocation more than consolation. Just recall the controversy that erupted last spring over the Time magazine cover that showed a 26-year-old mom breast-feeding her 3-year-old son ? a portrait that was inspired by images of the Madonna and Child. **Note: this image is not available to download.

Even as the number of breast-feeding mothers continues to grow, public breast-feeding is still a source of provocation more than consolation. Just recall the controversy that erupted last spring over the Time magazine cover that showed a 26-year-old mom breast-feeding her 3-year-old son – a portrait that was inspired by images of the Madonna and Child. And women who try to suckle their infants in church are often met with hard stares rather than a friendly welcome.

Whatever the obstacles, Miles thinks it would be a good thing for the culture, and Christianity, if Maria Lactans made at least a brief return to church – at Christmas or anytime.

“I think there should be a plethora of symbols of God’s love for humanity,” she said. “Can there be only one way to talk about so great a mystery? No, there can’t.”

KRE/AMB END GIBSON

![RNS photo courtesy www.cattoliciromani.com [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://religionnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/thumbRNS-BREASTFEED-JESUS121112a.jpg)