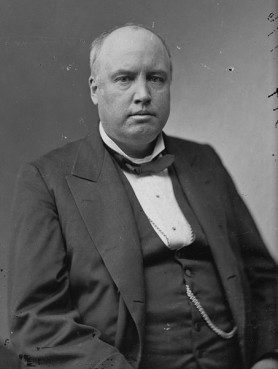

Robert G. Ingersoll. Library of Congress description: “Ingersoll, Robert (The Infidel)”. Photo courtesy Wikimedia Commons Public Domain (http://bit.ly/KODsv3)

(RNS) Meet Robert Ingersoll, the most famous American atheist you’ve probably never heard of.

A self-educated attorney and atheist, Ingersoll was a Victorian-era rock star who could pack theaters from Texas to New York with people who came from hundreds of miles around to hear “The Great Agnostic” lecture against religion.

He was courted by politicians, his likeness was carved in stone, and when he died in 1899, newspapers around the country carried his obituary. A Civil War veteran, he was buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Today, Ingersoll is largely unknown outside atheist circles. But he’s enjoying a bit of a revival, with a critically-acclaimed new biography, a walking tour of Ingersoll sites, a growing number of visitors to his birthplace and an oratory contest in his name.

Ingersoll enthusiasts say the recognition is overdue because the issues he championed remain hot topics — freedom of speech, civil rights, women’s reproductive freedom and, especially, the role of religion in government.

And he did it with flair. Ingersoll had the intellect of the late atheist Christopher Hitchens and the crowd appeal of “The Daily Show” host Jon Stewart.

“Ingersoll was the perfect humanist,” said Steve Lowe, founder of the Robert Ingersoll Oratory Contest, which will be held in Washington on June 30. “He was very engaging as a speaker because he used humor and he was outrageous in that he would speak against religion with such fervor.”

“All of that was very titillating, and people would go to hear him whether they agreed with him or not. He did not respect religion, but he respected people who were religious.”

It’s the respect that Ingersoll held for those he disagreed with that has some atheists, humanists, skeptics and other nonbelievers saying that Ingersoll is especially ready for resurrection.

“Ingersoll didn’t agree with liberal religionists any more than he did with fundamentalists, but he believed in alliances on the issues that liberal religious people agreed with him on,” said Susan Jacoby, author of “The Great Agnostic,” an Ingersoll biography published in January that, in part, takes contemporary atheism to task for allowing him to be forgotten.

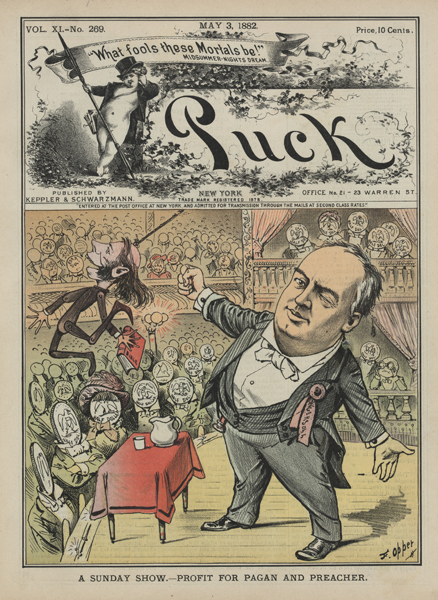

Print shows Robert G. Ingersoll speaking from a stage in an auditorium filled with an audience whose heads are half-dollar coins; dangling from a cord at the edge of the stage is Thomas De Witt Talmage as a marionette or wooden toy, with one hand pinned to the Bible. Photo courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington

“I don’t think we have many prominent figures in the atheist movement today who are ready to form public alliances on issues they support, like gay rights and issues affecting women, and I believe we need a lot more of them.”

Ingersoll was born in 1833 in upstate New York, the son of an itinerant Methodist minister. Like Abraham Lincoln, he was largely self-taught. Yet unlike Lincoln, who also had unconventional ideas about organized religion, Ingersoll was public about his lack of faith, something historians like Jacoby believe curtailed his high political ambitions.

Ingersoll also didn’t found an organization to continue his agenda after his death, which may also explain his faded prominence.

But Tom Flynn, director of the Robert Green Ingersoll Birthplace Museum in Dresden, N.Y., says that trend may be reversing. He has seen a rise in visitors to the museum’s website in recent months, and hopes to host an Ingersoll conference next year.

“When you read his stuff today he is amazingly eloquent and he does a fabulous job of capturing what it means to live with reason and compassion without a fear of hellfire,” Flynn said. “And as we have this growing number of young people moving away from organized religion, I think Ingersoll is a voice that when they discover him he feels surprisingly modern.”

That’s what happened to Lowe, the contest organizer. When he left his Methodist faith for humanism, he read today’s standard pantheon of “New Atheist” authors – Richard Dawkins, Hitchens and Sam Harris. But when he discovered the collected speeches of Ingersoll, something grabbed him.

“His words are still beautiful to hear, and of course he was a leader in criticizing organized religion and he advocated for Darwin, evolution and science,” Lowe said. “The freethought community is always looking for a model to put up as an admired free thinker, and we think Ingersoll deserves more attention not just for historical purposes, but also because he is still applicable to issues we are still navigating.”

Lowe became so enthusiastic about Ingersoll he revived a defunct walking tour of Ingersoll sites in Washington that includes the U.S. Capitol, where Ingersoll argued before the Supreme Court (then meeting in the Old Senate Chamber), and Lafayette Square, where Ingersoll lived.

Two years ago, he founded the oratory contest, held in Washington’s Dupont Circle neighborhood. This year, the contest hit its maximum of 15 contestants within a month of being announced and now has a waiting list.

Jamila Bey, a Washington-based journalist and commentator, took second place in the oratory contest two years ago with a recitation of Ingersoll’s “What I Want For Christmas” speech, delivered in Boston in 1897. She said Ingersoll has as much to say to the freethought community today as he did 100 years ago.

“I think he would say to us, ‘Keep talking,’” she said. “I think he would remind us that we can never become complacent. I think he would say it is about more than freethought, it’s about genuinely claiming our place at the table of American ideas.”

KRE/LEM END WINSTON