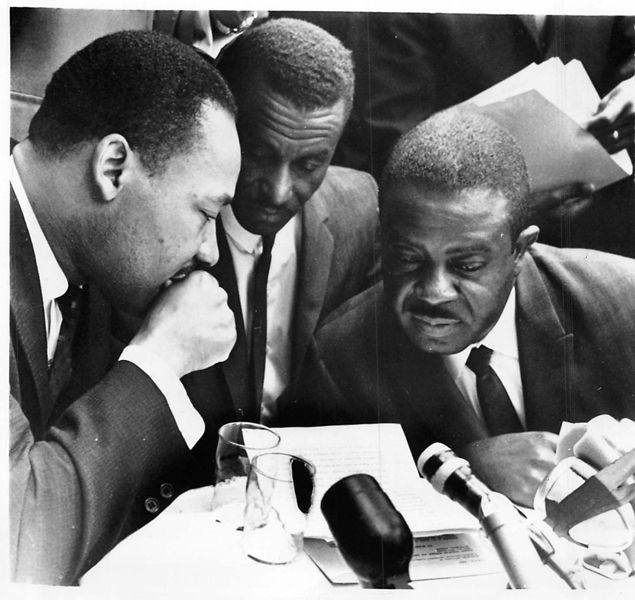

(May 10, 1963) The “Big Three” of the civil rights movement put their heads together here just before releasing a statement that accord had been reached on their grievances. (Left to right) The Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.; the Rev. Fred Shuttleworth; the Rev. Ralph Abernathy. Religion News Service file photo

(RNS) It may be the most famous speech of the 20th century.

Millions of American schoolchildren who never experienced Jim Crow or whites-only water fountains know the phrase “I have a dream.”

And many American adults can recite from memory certain phrases: the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s use of the prophet Amos’ vision of justice rolling down “like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream,” or the line about children being judged not by “the color of their skin but the content of their character.”

Emblazoned on T-shirts, reprinted on posters and in textbooks, the speech has become an iconic part of the American experience. As the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington approaches Wednesday (Aug. 28), many Americans will participate in a series of events, including a commemorative march on Saturday.

To many in this country, “I have a dream” has a place of honor next to the Declaration of Independence, the Emancipation Proclamation and the Gettysburg Address. It celebrates the lofty ideals of freedom.

Over the years, the speech has become part of the nation’s civil religion — a set of beliefs, and rituals that are partly religious and partly political and inform the country’s core values of freedom, equality and rule of law.

Its place in America’s common creed is perhaps best symbolized by the oversize statue of the slain civil rights leader on the National Mall, not far from the Lincoln Memorial where he delivered his famous oration.

But scholars say it would be a mistake to celebrate the speech without also acknowledging its profound critique of American values.

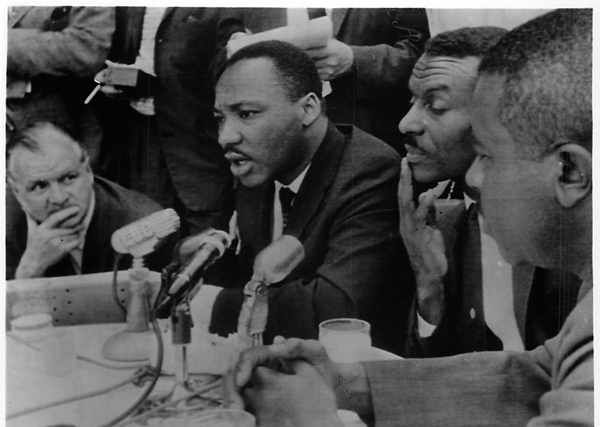

(1963) A truce in Birmingham’s racial strife comes as the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and associates call a temporary halt to mass demonstrations and “freedom marches” in the Southern city. King said he believed honest attempts were being made by white business leaders to settle racial differences. With him are the Rev. Fred L. Shuttlesworth, head of the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights (second from right), and the Rev. Ralph D. Abernathy, King’s chief assistant. Religion News Service file photo

“On the one hand, he appeals to Scripture and the Constitution,” said Josef Sorett, professor of religion and African-American studies at Columbia University. “At the same time he’s also critiquing those texts because the nation has not lived up to what it professes to be.”

King begins his speech “Five score years ago” echoing Lincoln’s famous “Four score and seven years ago” from the Gettysburg Address.

He then talks of coming to the nation’s capital to cash a check, a promissory note that the country owes blacks because of the Declaration’s promise that all men are created equal and have inalienable rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

But there’s a subversive subtext in that promise; the founders never envisioned equality for African-Americans.

“King embraces American values not to celebrate it, but to point out that we’ve never fulfilled those values,” said Jonathan Rieder, a sociologist at Barnard College and the author of “Gospel of Freedom: Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Letter from Birmingham Jail and the Struggle That Changed a Nation.”

“He’s saying if you believe these things, then you have to act to cure your sinfulness.”

Historians of the era say King was angry with government, churches and society for their unwillingness to challenge black inequality. But as he prepared his speech on the Mall, he had to dial it back for pragmatic political reasons, including the Kennedy administration’s initial opposition to the march.

“King didn’t want to do anything that was going to spoil the chances of the civil rights bill or create a backlash with Congress,” said Rieder.

And so he wrote the address with Congress and Northern white supporters in mind.

Like other statesmen before him, he frames the struggle to achieve equality in religious terms, by invoking the book of Exodus, the account of God guiding the Israelites out of slavery in Egypt and toward the Promised Land.

“One hundred years later, the Negro is still languishing in the corners of American society and finds himself an exile in his own land,” King said.

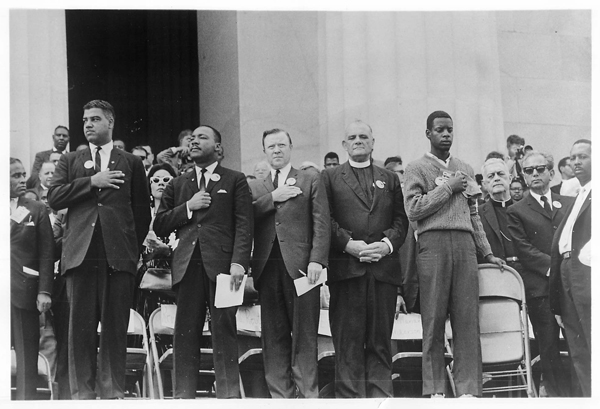

A young usher, holding cap at right, stands solemnly with religious, civil rights and labor leaders on the platform in front of the Lincoln Memorial during the national anthem at the opening of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom program on Aug. 28, 1963. Five of the 10 chairmen of the march also on the platform were, from left to right: Whitney M. Young Jr., executive director of the National Urban League; the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference; Walter P. Reuther, president of the United Automobile Workers Union; the Rev. Eugene Carson Blake, chief executive officer of the United Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A., and acting chairman of the National Council of Churches’ Commission on Religion and Race; and, second from right, Rabbi Joachim Prinz, president of the American Jewish Congress. Religion News Service file photo

But in the second and most popular part of the speech, King abandoned his careful notes and swerved into a call-and-response motif from the black church — the “I have a dream” sequence.

Scholars say this dream sequence did not originate in Washington. King had delivered versions of it in such cities as Rocky Mount, N.C., and Detroit. It was a part of his repertoire that year.

Invoking the biblical prophets Isaiah and Amos, the sequence marks a shift toward the future where King invokes God’s vision for America.

Just as the prophets were called seers, “one has the sense King is seeing things the rest of the country can’t make out,” said Richard Lischer, professor of preaching at Duke Divinity School who wrote a book on King. “He’s looking out on the horizon with a prophetic imagination we don’t have.”

In that famous sequence, King sees a future where the descendants of former slaves and former slave owners can share a meal, where white and black children can walk together as brothers and sisters.

Neither of those things was possible in 1963, especially in the South with its segregrated restaurants, schools, movie theaters, basketball courts and swimming pools.

“The celebration of ‘I have a dream’ often has as its condition a failure to take seriously the prophetic vision that was central to King that was not comforting, was not convenient, was full of rebuke and didn’t celebrate the nation,” said Rieder.

And while some might point to President Obama’s election as proof that the dream has been realized, many scholars point to disparities between whites and blacks in education, employment and incarceration as proof that there’s still a lot of work to be done.

The speech is even more significant now, said Lewis Baldwin, a professor of religion at Vanderbilt University “because poverty is much more pervasive than it was in King’s time. Homelessness is much more pervasive than the problem was in King’s time.”

“The American dream is still something that we have to work toward and we have to struggle for,” added Baldwin. “We have to be on a mission to achieve it.”

KRE/AMB END SHIMRON