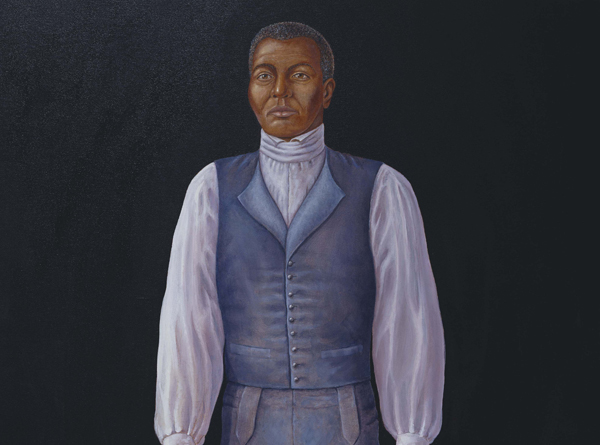

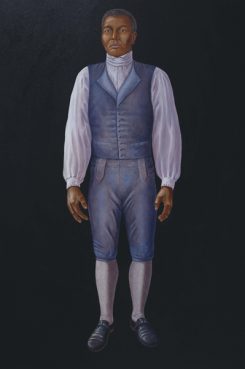

A painting of Fortune by William Westwood, a medical illustrator, based on Fortune’s skeleton. Photo courtesy Mattatuck Museum

WATERBURY, Conn. (RNS) The remains of an 18th-century Connecticut slave whose abuse continued long after his death will finally be given a dignified burial.

On Sept. 12, more than two centuries after his death, a slave known as Fortune will be interred at Waterbury’s Riverside Cemetery with all the trappings of a state funeral.

It will be a ceremonial end to the life of a man whose mistreatment serves as a reminder of the North’s participation in slavery.

Fortune died in 1798. His death is clouded in lore and speculation. Did he drown in the Naugatuck River? Was he fleeing and fell and broke his neck?

What is certain is that Fortune’s master, a Waterbury bone doctor by the name of Preserved Porter, stripped Fortune’s skin, boiled his bones and used his skeleton as a medical specimen. The mistreatment of the slave was recorded in a book about Waterbury’s history by Joseph Anderson.

The indignity continued well into the next century. Porter is believed to have opened an anatomy school in Waterbury where bone surgeons studied Fortune’s skeleton. In 1910, the slave’s skeleton surfaced in a closet in a Waterbury building.

It was then donated to the Mattatuck Museum in Waterbury where it hung in a glass case with the name “Larry” scrawled on its skull, horrifying and entertaining curious schoolchildren on field trips. Museum curators realized the display was in poor taste and took it down in the 1970s.

There he remained boxed up, his story untold, until museum officials began researching the history of African-Americans in Waterbury and received a letter from a city resident urging them to look into “Larry” the skeleton at the museum.

What followed was a decades-long Fortune Project for the museum as scientists and anthropologists examined and studied Fortune’s bones, most recently Quinnipiac University. All the while, many debated how best to serve his legacy.

For Maxine Watts, the chair of the African American History Project, which partnered with the museum, Fortune’s bones serve as a reminder of the flawed slave ideology that considered African-Americans subhuman.

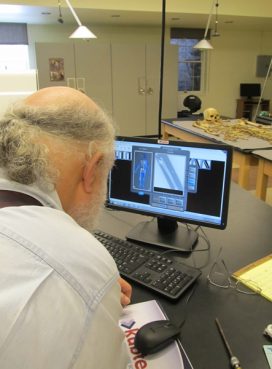

Professor Gerald Conlogue, co-director of the Bioanthropology Research Institute at Quinnipiac University X-raying the bones of Fortune, an African-American slave from the 1700s to find out as much as he can about him before he is buried. Photo courtesy Mattatuck Museum

“His living and his death were not in vain,” said Watts, former president of the Waterbury chapter of the NAACP. “Slaves were not considered totally human. Yet Fortune’s bones were used as a teaching tool for human anatomy. Fortune is proof that we are all equal underneath the skin.”

The Rev. Amy Welin, who will preside over Fortune’s funeral at St. John’s Episcopal Church in Waterbury, said the way the slave’s master used his bones is hard for her to fathom, even after studying the cruelty of slavery. Fortune was baptized in St. John’s in 1797, where Porter’s wife, Lydia was a member.

Welin said she won’t eulogize Fortune’s life, but will preach about God’s justice.

“The service will be for the rest of us,” she said. “What are we supposed to do with what we’ve learned about Fortune? What are we supposed to do with the racial injustice around us now, the ghosts of slavery that still haunt us?”

Fortune and his wife, Dinah, had four children. But because Fortune’s descendants can’t be found, members of the Southern Connecticut chapter of the Union of Black Episcopalians will accompany his casket down the aisle of the church during the funeral.

Steven R. Mullins, a founding member of the chapter, will serve as master of ceremonies during the funeral.

“I hope that the Waterbury community comes out to the burial,” said Mullins. “I hope people realize that there was slavery in Connecticut. Fortune’s burial will be a learning and teaching moment.”

Connecticut abolished slavery in 1848, but it provided gradual emancipation for persons who turned 25 prior to 1784.

The funeral will be held at 4 p.m. Sept. 12 at St. John’s Episcopal Church.

YS/AMB END SOMMA