NEW YORK (RNS) From its historic black churches to large Jewish enclaves to landmark Catholic and Protestant churches, New York City is the ultimate religious melting pot. And now, overseeing it all is a new mayor whose only religious identity seems to be “spiritual but not religious.”

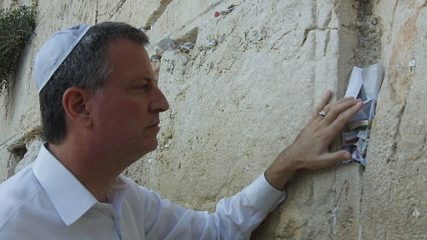

Mayor Bill de Blasio is now perhaps the nation’s most visible “none,” an icon of one of the nation’s fastest-growing religious groups — those without any formal religious identification.

His election could reflect a new kind of American politician — one who is shaped by religion and religious values but is not expected to talk about or bow to religion as in years past, said Jennifer Jones Austin, co-chairwoman of de Blasio’s transition team and the daughter of a pastor.

“What drives him are his fundamental beliefs about liberation theology when it comes to social justice, our responsibility to care for all who are on this earth,” Jones Austin said. “I heard him on several occasions say ‘Amen’ when he felt very strongly about something.”

The mayor has taken great effort to reach New York’s many religious traditions, Jones Austin said, even as he was criticized for initially not including Catholic clergy on his 60-member transition team.

Now, de Blasio will have to navigate the lack of his own religious identity within a religiously diverse city.

“When I met him, however briefly, he told me he had been baptized and raised a Catholic and he was very proud of the fact that he had an uncle, a priest. What his religious status or health is now, I don’t know,” New York Cardinal Timothy Dolan told New York’s ABC affiliate.

“Would you try and bring him back into the fold?” ABC host Diana Williams asked Dolan.

“Oh I try to bring everyone back!” Dolan said. “So if he indicates he’ll have an interest, I’ll be knocking at the door.”

Liberation theology’s influence

In the 1980s, de Blasio worked with Sister Maureen Fiedler and others at the Maryland-based Quixote Center, organizing a project called “The Quest for Peace,” focused around development and humanitarian aid for Nicaraguans during the nation’s bloody civil war. At the time, liberation theology was a frequent topic of conversation, Fiedler said.

Liberation theology came of age in the 1960s and ’70s as a Catholic response to the Marxist movements that fought Latin America’s military dictatorships in those decades. It affirmed that, rather then just focusing on seeking salvation in the afterlife, Catholics should act in the here and now against unjust societies that breed poverty and need.

“We lived and operated in the spirit of liberation theology, the idea that we’re called to enact justice for the poor,” said Fiedler, who now runs her radio show, Interfaith Voices, out of the Quixote Center.

After years of isolation in Rome, that theological current is finding renewed acceptance under Pope Francis, observers say. Fiedler said de Blasio referred to the pope in a brief conversation during the inauguration.

“He said to me and (another former colleague), ‘Are you responsible for what Pope Francis is saying? It sounds familiar,’” she said.

De Blasio’s grandparents immigrated to the U.S. in 1905 from Italy. His father struggled with alcoholism, left his family and died by suicide. De Blasio has cited his mother, Maria, as the single most influential person in his life, even taking her maiden name as his own.

“Although my mother was raised a Catholic, she did not bring me up in the Church,” he said on an online forum on Reddit. “I considered myself a spiritual person but unaffiliated, and I was definitely very influenced by the liberation theology movement in Latin America. And BOY am I a fan of Pope Francis!”

Politicians claiming religious influence without a specific connection to a tradition might be worse than saying “I’m not interested in religion,” said Rabbi Brad Hirschfield, president of CLAL–The National Jewish Center for Learning and Leadership, a New York-based think tank.

“Blandly saying ‘I’m spiritual but not affiliated’ won’t work,” said Hirschfield. “He has to put some meat on those bones.” About one in five Americans now consider themselves to be “nones,” according to the Pew Research Center.

Hirschfield also worries that de Blasio’s association with liberation theology is too distant to claim real affiliation. “To simply say you’re a fan of liberation theology and you were influenced by it is so simplistic,” he said. “We need to give politicians room to say ‘Religion doesn’t work for me.’”

Bloomberg’s ‘blind spot’

Before his departure, Mayor Michael Bloomberg navigated several issues with religious leaders during his three terms in office, always with an inclination to keep religion and politics separate.

Bloomberg, who is Jewish, declined to feature clergy at 9/11 commemorations and strongly defended a proposal to build an Islamic community center near Ground Zero. He also supported New York Police Department surveillance of Muslim mosques and neighborhoods.

De Blasio said Bloomberg governed with a “blind spot” to faith-based groups. “I don’t think the mayor really understands how crucial it is to protecting the fabric of the city,” de Blasio said in an interview with The New York Times.

During his campaign, de Blasio broke with his predecessor on controversial issues, saying he would roll back Bloomberg’s efforts to keep churches from renting space in public schools, work with Jewish leaders to ease the city’s supervision of circumcision rituals and accommodate two of the most important Muslim holy days.

During his campaign, de Blasio received strong support from voters of all major religious groups, said Tony Carnes, editor of the website A Journey through NYC religions.

Protestants and smaller religious groups were the most inclined toward the Democratic nominee, according to an exit poll conducted by Edison Research. Evangelicals and Pentecostals played a pivotal role in pushing de Blasio ahead of the other candidates in the Democratic primary.

If de Blasio can avoid some controversies that dogged Bloomberg, Carnes said, he could cement a strong religious voting bloc in future elections. For instance, the city has debated requiring pregnancy centers to post signs that they do not perform abortions. And the “stop-and-frisk” police tactic, which some argued resulted in racial profiling, remains controversial, especially in the city’s influential black churches.

“This is the first election that we know of in recent times that Protestants decided who is mayor in New York,” Carnes said. “From the planning of his leadership, he has signaled that he’s faith interested and faith friendly.”

KRE/AMB END BAILEY