PUNE, India (RNS) The large crowd of followers shouted, “Osho! Osho! Osho!” as Kundalini meditation started. For me, Osho became “Oh-no!”

Student journalists from the University of Southern California pose for a photo with their professor outside of the Osho International Meditation Resort on March 15. Photography inside the resort is forbidden. (Left to right front row, Professor Diane Winston, Alexandra Babiarz, Grace Lim and Chhaya Nene; left to right back row Rosalie Murphy, Graham Clark and Katherine Davis.) Photo courtesy of Chhaya Nene

If I chanted his name would I betray my faith? Hindus believe prayers can reach God in whatever form, be it Allah or Jesus or Shiva. Osho wasn’t God, so was chanting his name OK? I decided against it. I wasn’t quite ready to let go of everything I knew.

I was dressed head to toe in the mandatory floor-length maroon robes, like the more than 100 spiritual seekers from Russia to South America and from Japan to the U.S. who were also there that day. Yet I felt I didn’t blend in. My brown skin stuck out against the paler shades in the room. I was reminded of something I had known all along. I have always had one foot in the American world, and the other firmly entrenched in my Indian roots.

I had no idea whether I was ready for the Osho International Meditation Resort. But chanting a name other than the divine ones I believe in felt wrong.

The resort is tucked away in Koregaon Park, one of the most prestigious residential areas in the city. Wealth is evident in the elegant white houses that nestle among trees, fields and peacocks strutting on the grounds.

This wasn’t the Pune I had spent time visiting as a child. This felt opulent, and even ostentatious.

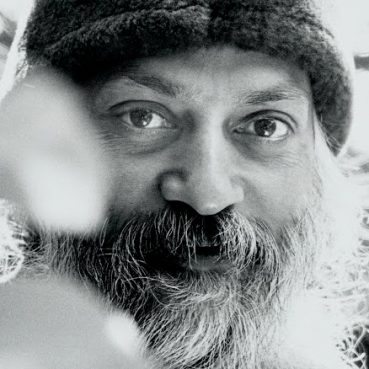

In 1974 Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, a philosophy professor turned mystic and sex guru, founded an ashram in Pune that attracted thousands of spiritual seekers. After trouble with the local authorities, Rajneesh decamped for the U.S., where he established a controversial commune in Oregon. Charged with immigration fraud and bioterrorism, Rajneesh was deported from the U.S.

In 1974 Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, a controversial philosophy professor turned mystic and sex guru, founded an ashram in Pune that attracted thousands of spiritual seekers.

He and his followers eventually returned to Pune. Rajneesh took on the name Osho (Buddhist high priest), reflecting the increased focus on Zen in his discourses. The controversial guru, who died in 1990, renamed the ashram the Osho International Meditation Resort.

As my mind raced through this multicolored history, I heard that chant, “Osho! Osho! Osho!” Kundalini meditation had begun.

“Shake your body, but don’t will the shake. If you will the shake you won’t enjoy it, and if you enjoy it, you won’t be willing it,” a young British voice boomed out from a loudspeaker projecting Osho’s teachings.

I looked around anxiously. There they were. My classmates, my professor and a sea of people who had come to “find their true selves” through partaking in an active meditation. But I actively resisted.

Would joining this strange ritual mean I was abandoning my Hindu heritage? Would it make me some kind of an Indian freak? Was I idolizing a bearded old man who had taken things too far?

I saw an Indian couple who told me they had come for a weekend escape. They were shaking to bells and started dancing with no patterns. Slowly I found my inhibitions melting away.

When the dancing stopped and silent meditation began, I realized that I had never been able to surrender to a religious or spiritual experience without putting up both emotional and mental walls.

Osho’s meditations were unlike any Hindu meditation I was taught as a child. Meditation was always a silent act. The focus is on the third eye and saying the word “Aum.” That was my social conditioning. That was Hinduism.

Osho’s teachings are not Hinduism; he had rejected all institutionalized religion.

But there are echoes of religion in his system, and if Hinduism encourages embracing all different cultures and experiences, I was going to do it.

I decided I would do what the voice coming from the speakers told me. I would open my mind and embrace the experience.

The soft music coming from the speakers now sounded like a roar. My other senses became keener too.

As I let my mind wander, I could see what a drop of water looks like. I saw what happens when water droplets make contact with the ground and explode, the swimming path of catfish and the slow growth of a plant.

I was so deep within this mental state that I felt as though I was having an out-of-body experience. It made me excited and scared at the same time.

I had taken a step into the spiritual and religious world through meditations and reached a higher level of consciousness. I had come to a new level through Osho’s teachings.

All of a sudden it didn’t matter that I was Indian-American or that this wasn’t Hinduism. I had tapped into a new spiritual plane and I could see its appeal.

For the first time I was able to connect with some part of myself where all the stressors in my life seemed unimportant. Homework? Exams? Trying to make everyone happy? Running five minutes behind schedule?

Were all those things really important anymore?

I had found a small nugget of peace, something I could hold onto when life began to spin out of control. And that was invaluable.

Maybe Osho wasn’t Hindu, and maybe his methods were unorthodox, but my experience was real.

Osho wasn’t brown enough for me, and maybe I wasn’t brown enough to understand why some Indians wanted to escape to this place and to chant his name.

But I was ready to ready to stop worrying about shades of brown and focus on the maroon.

(Chhaya Nene is a graduate student at the University of Southern California and traveled to India recently as part of a class trip.)

YS/MG END NENE