(RNS) With presidents flocking to the Lyndon B. Johnson Library in Austin, Texas, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the civil rights laws that permanently changed America, it would be easy to forget the extraordinary role religious communities played in that struggle.

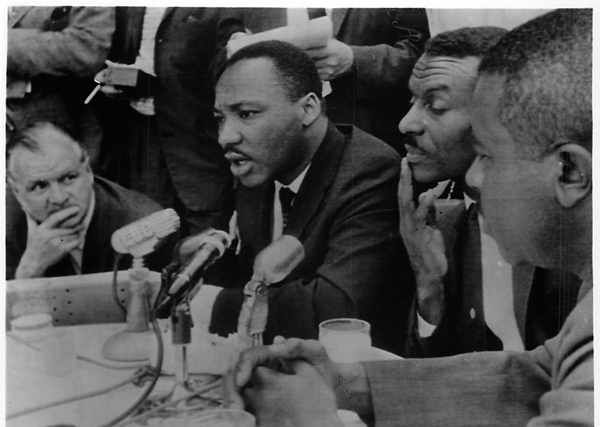

(1963) A truce in Birmingham’s racial strife comes as the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and associates call a temporary halt to mass demonstrations and “freedom marches” in the Southern city. King said he believed honest attempts were being made by white business leaders to settle racial differences. With him are the Rev. Fred L. Shuttlesworth, head of the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights (second from right), and the Rev. Ralph D. Abernathy, King’s chief assistant. Religion News Service file photo

But they must not be overlooked, especially the clergy who pressed Congress and the White House to support civil rights legislation and who enlisted their often-reluctant faith communities and congregations to join in the war against discrimination.

The most prominent Christian leader, of course, was the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel was also a high-profile active participant in the movement. In 1965, he marched alongside King in Selma, Ala., and later wrote: “When I marched in Selma, my feet were praying.”

If King and Heschel were the “generals” in the civil rights war of the 1960s, I was a foot soldier in the army of pastors, priests and rabbis. In February 1964, my specific “battleground” was Hattiesburg, Miss., where by day I participated in a voting rights march in front of the Forrest County Courthouse. At night, inside the Morningstar Baptist Church, I assisted disenfranchised blacks in voter registration classes.

The congregation hailed the white ministers and rabbis as heroes, and Morningstar’s choir serenaded us with stirring freedom hymns. The church’s pastor preached liberation sermons, many linked to the Exodus story of Israelite slaves fleeing Egyptian slavery.

Here’s what Hattiesburg looked like in 1964: Forrest County Registrar Theron C. Lynd decided who could vote and who could not. He made certain that nearly all eligible whites were registered, while only 12 of 7,500 potential black voters could cast ballots. Not surprisingly, Lynd was the defendant in litigation brought against him by the federal government for voter suppression.

A clear double standard operated back then. Whites had little or no trouble enrolling, but Mississippi blacks often faced the obstacle of complex literacy tests that included arcane sections of the state constitution. All that changed with the urgently needed civil rights legislation of the 1960s.

My clergy colleagues and I slept in a hastily created “dormitory” in the rear of a local appliance repair shop. The shop’s black owner was aptly named “Mr. Friendly.” We could never be sure whether the temporary shower would spout hot water or the toilet would flush properly.

Each morning we marched single file to the courthouse, where we placed poster boards around our necks with messages demanding freedom and voting rights. Joined by blacks from Hattiesburg, we began three hours of picketing Lynd’s bastion of resistance. After a brief lunch break — always staying together for safety and personal security — the rabbis and ministers spent another three hours in the afternoon marching and providing blacks the physical protection required to climb the courthouse steps in an effort to become a registered voter. The success rate was extremely low; it improved only after the passage of the civil rights legislation.

Like troops in a war zone, we encountered “enemy resistance” in the form of well-dressed men and women from the local White Citizens’ Council. They frequently walked alongside us, hurling taunts and curses. Someone spit on me and let loose a verbal burst of anti-Jewish pejoratives. When the courthouse closed at the end of the day, we marched together back to the Morningstar Church for dinner. The food, prepared by church members, was outstanding.

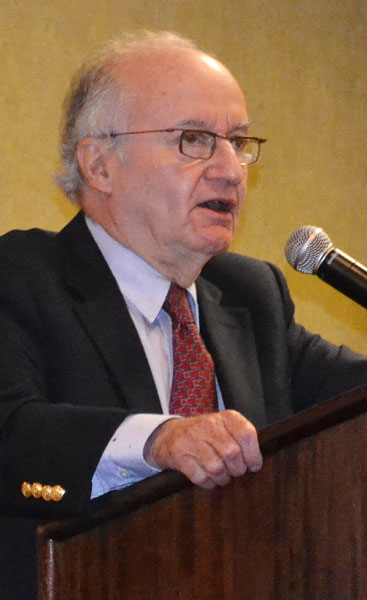

Rabbi A. James Rudin, the American Jewish Committee’s senior interreligious adviser, is the author of the recently published “Cushing, Spellman, O’Connor: The Surprising Story of How Three American Cardinals Transformed Catholic-Jewish Relations.”

The white clergy were always tense and cautious while marching, but once we returned to the black area of Hattiesburg, we felt secure. Others during that tumultuous era, however, were not so fortunate.

Four months after my “tour of duty” in Mississippi, three young civil rights workers — Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner, both Jewish, and James Chaney, a black Mississippian — were murdered in Neshoba County. Vernon Dahmer, the Hattiesburg NAACP leader who befriended the white clergy, was killed when his house was firebombed in 1966. It was not until 1998 that KKK leader Samuel Bowers was finally sent to jail for killing Dahmer.

My time in the civil rights trenches is embedded in my personal memory bank. It’s a bitter chapter in our nation’s history that must never be forgotten.

(Rabbi A. James Rudin, the American Jewish Committee’s senior interreligious adviser, is the author of the recently published “Cushing, Spellman, O’Connor: The Surprising Story of How Three American Cardinals Transformed Catholic-Jewish Relations.”)

KRE/MG END RUDIN