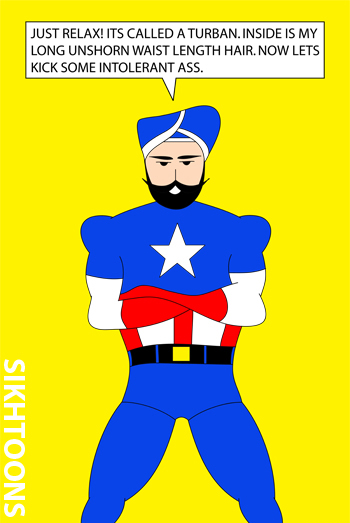

CAPE TOWN (RNS) “Just relax! It’s called a turban. Inside is my long unshorn waist length hair. Now let’s kick some intolerant ass.” That’s the caption floating above Vishavjit Singh’s drawing of a turbaned, bearded Captain America on his website Sikhtoons.com.

Singh, who is Sikh, is a software engineer by day, pretend superhero by night. He’s also one of many cartoonists using art to fight religious intolerance, hatred, stereotypes and censorship attempts online.

Vishavjit Singh’s drawing of a turbaned, bearded Captain America. Photo courtesy of Vishavjit Singh

Singh is based in New York City and launched Sikhtoons in the wake of 9/11. He says his inspiration came from political cartoonist Mark Fiore, whose work challenged hatred directed at Muslims and Sikhs after the attacks.

“Initially some of my cartoons were based on my own experience as a bearded, turbaned American on the streets of New York, where people would shout ‘Osama,’ ‘Taliban,’ ‘Go back home,’” Singh said. “I’d also respond to hate crimes against Sikhs in the news.”

Singh has since branched out to create “work that addresses or engages Americans who don’t know who I am or what Sikhs are, using humor to make them approach me.”

Imitating his own art, Singh sometimes dresses up as Captain America, roaming the streets of New York City and engaging with strangers to challenge stereotypes and misperceptions about his faith.

Once constrained to the opinion pages of local newspapers, satirical cartoons now reach global audiences online, racking up retweets, “likes” and plenty of vitriol.

In 2005, Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten published 12 editorial cartoons depicting the Prophet Muhammad, a blasphemous act according to many interpretations of Islam. The incident sparked global outrage and protests, contributing to more than 100 reported deaths.

A political cartoon by Martin Rowson that appeared in The Guardian in January 2010. Photo courtesy of Martin Rowson

British cartoonist and free speech advocate Martin Rowson, who identifies as a “visual journalist,” produced his own cartoon in response to the Jyllands-Posten controversy and subsequent censorship attempts. The cartoon shows a bearded man in a turban opening a copy of Jyllands-Posten saying “Looks nothing like me…”

Rowson, who is an atheist, has been a professional cartoonist for 32 years. The more people his cartoons reach online, the more complaints and death threats he receives.

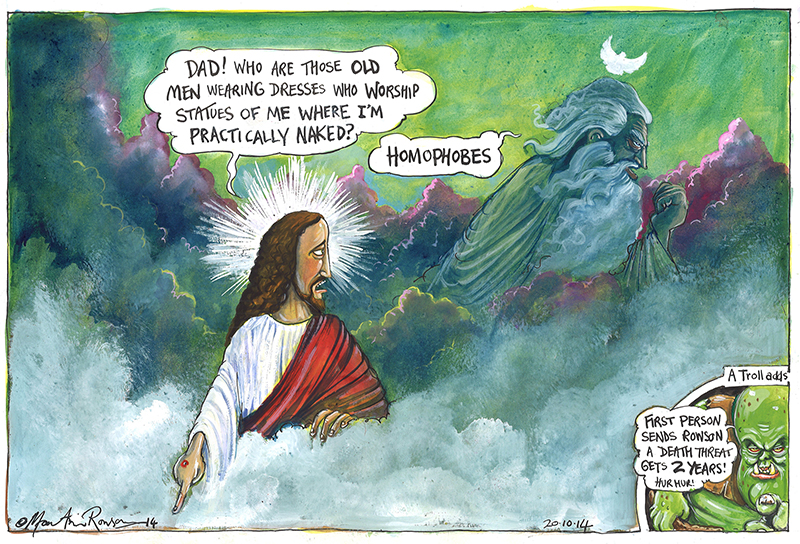

One published in October depicts Jesus and God the Father engulfed in clouds. Jesus, pointing below, asks, “Dad! Who are those old men wearing dresses who worship statues of me where I’m practically naked?” “Homophobes,” God responds.

One of Martin Rowson’s cartoons depicting Jesus and God the Father in the clouds. Photo courtesy of Martin Rowson

In the lower corner of the frame, a green troll points to the reader, adding, “First person sends Rowson a death threat gets 2 years!” a critique of Britain’s justice secretary’s plan to increase jail time for Internet trolls who spread “venom” on social media.

Rowson’s cartoons are regularly published in the British paper The Guardian.

“It’s a huge audience, but not everyone is used to the British industry of cartooning, which is among the most vicious in the world,” Rowson said. “I’ve gotten thousands of truly abusive emails from America, and the same from Israel. I think I’ve probably offended everyone across the spectrum.”

In 2007 Rowson went after fellow atheists Richard Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens, depicting Dawkins as a starry-eyed cult leader and Hitchens as morbidly obese, holding a sign that reads “OUT ‘n PROUD!!” Rowson said the cartoon was a commentary on a public campaign Dawkins backed encouraging atheists to “come out of the closet.”

Catholic cartoonist Jason Bach views his Catholic Cartoons series as a form of evangelization. He deliberately avoids controversial topics such as abortion, contraception, gay marriage and clergy sex abuse but still faces online backlash for tongue-in-cheek work.

An excerpt from “Frank & Ben” series by Jason Bach.

One cartoon, “Frank & Ben: Holy Rome-Mates,” opens with Pope Francis asking Pope Benedict to clear out of their shared living room because Frank “brought a lady home.” Ben responds, “All right, but don’t keep me up all night like last time.” The final frame shows Pope Francis praying loudly to a statue of the Virgin Mary.

Reader comments include praise for his work, attacks on the church and criticism of Bach for being flippant or irreverent.

“Cartoons that are too pious just aren’t funny,” Bach said. “Doing something people find funny goes a long way to countering misperception of Catholics as stodgy, puritanical and uptight.”

Rowson, whose first cartoons predated the Web, said the art form works especially well on today’s social media platforms, where immediacy is prized. Bach and Singh agree.

“A cartoon only take a few seconds or just one second to make its point. If it makes it well, the connection is instantaneous,” Singh said.

In February, German newspaper Sueddeutsche Zeitung published a cartoon depicting Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg, who was raised Jewish, as a hook-nosed octopus devouring messaging service WhatsApp, which the company acquired. The image, which resembled anti-Semitic Nazi propaganda, was widely shared and decried on social media, prompting the newspaper to change it.

This social media response paled in comparison to what befell Ali Farzat, Syria’s most famous cartoonist. In 2011, masked gunmen beat Farzat and broke his hands, presumably for criticizing President Bashar Assad in his drawings.

“The only thing power cannot cope with is being laughed at,” Rowson said of the attack. “You win when you have the last laugh.”

YS/MG END PELLOT