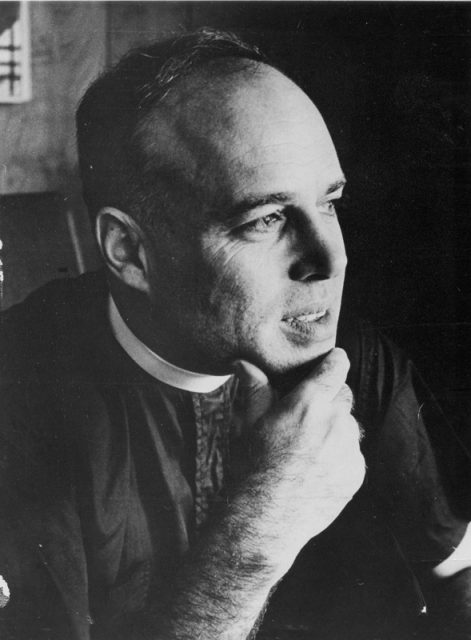

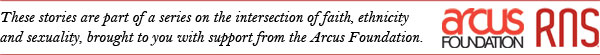

Malcolm Boyd at the height of his fame as author of “Are You Running With Me, Jesus?” Photo courtesy of Malcolm Boyd archives

(RNS) The Rev. Malcolm Boyd, who died on Friday (Feb. 27) at the age of 91, lived three lives — each extraordinary. More extraordinary still is how he gave each up for the next.

For the first third of Boyd’s life, he was an A-list producer in Hollywood’s golden age, most famously as a business partner of silent film actress Mary Pickford.

But in 1951, he gave up the glamorous life to become an Episcopal priest. His was an activist ministry. He was one of the Freedom Riders in 1961, he marched with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in Selma, got arrested for protesting the Pentagon. As Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel once recalled about Selma, he prayed with his feet — but Boyd maybe more so. Boyd’s renowned 1965 collection of contemporary prayers was called “Are You Running With Me, Jesus?”

And then, in 1977, he gave that life up too, coming out as gay and being scorned by his church and his community. But his activism was far from over.

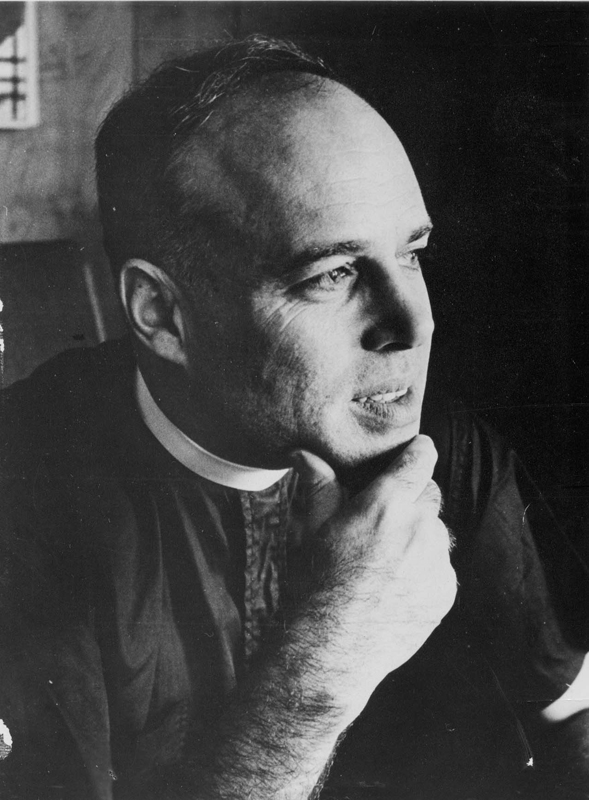

Malcolm Boyd with Mary Pickford at the Hollywood Advertising Club in 1949. Boyd was guest speaker and Pickford was guest of honor. Photo courtesy of Malcolm Boyd archives

Boyd held the first “AIDS Mass” in 1985. He and his partner Mark Thompson (his junior by 30 years — yet their intergenerational partnership lasted over two decades) were pioneers in the gay spirituality movement. And when their wedding was blessed at a Los Angeles cathedral in 2004, Boyd once again made the headlines.

I suspect most people haven’t heard of him, though. In his later years, Boyd wasn’t well known outside the gay community. He wrote 28 books, edited half a dozen more. But he may have fallen through the cracks. In the gay community, he may have been too religious to be lionized the way he should’ve been. Or perhaps too radical — the leading LGBT organizations didn’t mention his passing.

Beyond the gay community, progressive religious heroes — MLK excepted, of course — rarely get the recognition they deserve. But one gets the sense that Boyd and many others like him were a little too religious for the liberals, and too liberal for the religious. Maybe there’s something milquetoast about a liberal Episcopal priest.

But that wasn’t Boyd’s reality. His many transformations required enormous courage.

Last year, still blogging at age 90, he wrote in The Huffington Post that he was initially reluctant to join the civil rights movement. He “was scared about drawing undue attention to myself” both for reasons of humility and, surely, safety as well. As the film “Selma” aptly dramatizes, no one could predict what would happen at any particular demonstration. Even for someone with Boyd’s white and clerical privilege, death itself was a real possibility.

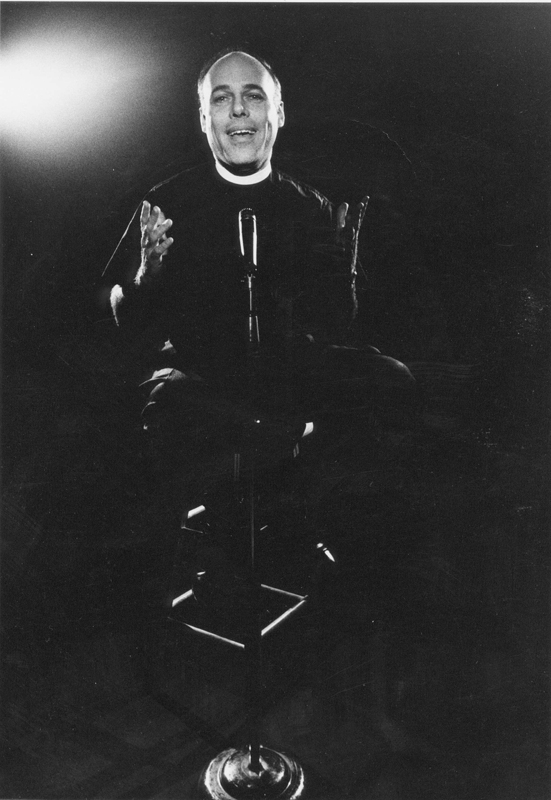

And then there was his cultural courage. An obituary in the gay publication Frontiers Media quotes a 1967 article describing Boyd as “a full time disturber of the peace, a jarring blend of Luther and Lenny Bruce, who is attempting to shock religion into being relevant.” Indeed, Boyd remained a creature of Hollywood, recording some of the prayers from “Are You Running With Me, Jesus?” with guitar accompaniment, and appearing onstage with comedian and activist Dick Gregory.

From the perspective of history, though, it’s probably his personal courage as a gay religious man that was his greatest trait.

Malcolm Boyd appeared at the San Francisco club “the hungry i” with comedian Dick Gregory in 1967. The two performed for a month at the famous club. Photo courtesy of Malcolm Boyd archives

Coming out in 1977 was, itself, a daring and costly move. But eventually, he and Thompson were among a group of gay male writers and thinkers who crafted a distinctively gay male (and, let’s face it, white gay male) form of spirituality that derived itself from one basic question: Does it matter that some people are gay? And if so, how?

For Thompson, Boyd, and others, gay men, by virtue of their perspectives and experiences, have distinctive roles in human society. Some of these derive themselves from gay men’s marginalization and stigmatization — Boyd himself was quite upfront about his own struggles with self-esteem growing up gay in the 1930s. Others, more controversially, have to do with the very nature of being a man with attributes usually associated with women: sensitivity, reluctance to fight, artistic sensibilities. Precisely the attributes that got gay men called “sissies” in school are those that color their perspectives in ways that enrich the entire human experience.

At its most extreme, gay spirituality can be essentialistic, proposing some universal “essence” shared by all gay men. Those that lack it (football player Michael Sam, or in-your-face military activist Dan Choi) just aren’t being true to their natures, critics say. They aren’t being gay “the right way.” It also arouses suspicions among some feminists; just because society deems something “feminine” doesn’t mean it is.

But even more reasonable iterations of gay spirituality can anger those LGBT activists who want to say that gay people are the same as everyone else. Love is love, right? We’re all the same, right?

Boyd’s message was, at its heart, more radical than this. It is radical to argue for the equal rights of women, LGBT people, African-Americans, and maintain that we are not all the same, that each of these groups (and many others) may see things differently from the norm they are supposedly assimilating into. That is not as likely to persuade conservatives and moderates. It’s a lot more scary to say “your system is wrong” than to say “let me into your system.”

So, even beyond the courage of a Hollywood player who became a priest, a priest who became a civil rights activist, and an activist who risked it all by coming out, Boyd had the courage of unpopular convictions. As he grew older, he grew into his wisdom, and it was easy to mistake him for being a kindly old man.

He was much more powerful than that.