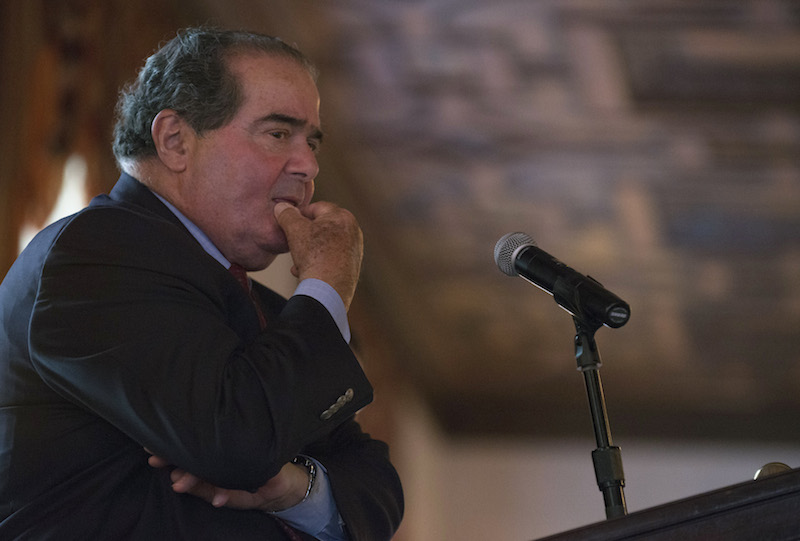

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia listens to a question after speaking at an event sponsored by the Federalist Society at the New York Athletic Club in New York October 13, 2014. Photo courtesy REUTERS/Darren Ornitz

(RNS) Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, who died unexpectedly Saturday (Feb. 13), approached the law with a clear (albeit controversial) legal philosophy about the First Amendment.

For decades, Scalia consistently argued that government could and should support religion. Over the past year, however, he adopted some unusual tactics to advocate for his position.

Last month, Scalia told a small audience in Louisiana that the government was not required to remain neutral on matters of religion. In fact, God, according to Scalia, had been good to America because of it.

Speaking at Archbishop Rummel High School in Metairie, La., Scalia said government can (and should) favor religion over nonreligion. He sharply criticized his colleagues on the court for their decisions to the contrary.

“Don’t cram it down the throats of an American people that has always honored God on the pretext that the Constitution requires it,” he said.

Scalia was the court’s clearest advocate for an accommodationist view of church-state relations. Accommodationists call for a limited reading of the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause, which states, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion.”

Scalia and other accommodationists agreed that the Establishment Clause prohibits the federal government from, say, supporting a national church. But as far as general support for religion, such as displaying the Ten Commandments in courtrooms or praying in public schools? This is perfectly compatible with the First Amendment.

Scalia blasted the court when it did not take this accommodationist view. In McCreary County v. ACLU, the Court ruled against a Ten Commandments display in a Kentucky courtroom, finding the display’s purpose was to advance religion. In a dissenting opinion Scalia said the majority had missed the point of the Establishment Clause: Honoring God and the Ten Commandments was not an endorsement of a particular religion.

RELATED STORY: How Scalia’s death affects key cases before the Supreme Court this year

He also raised these views in Lee v. Weisman, a case involving prayer at high school graduation ceremonies. Also dissenting in this case, Scalia panned the majority’s reasoning that school officials coerced students into praying as “incoherent,” and not true to an original understanding of the Establishment Clause.

Scalia wasn’t a passive jurist. Last term, he penned a rare rebuke after the court decided not to take on a case involving a school district renting church facilities for a school’s commencement activities.

Elmbrook Church, Wisconsin’s largest, was the site of multiple Elmbrook School District graduation ceremonies. In 2000, the district permitted a school to hold its graduation in the nearby church auditorium, due to poor facilities for such an event in the school. Some students and parents protested the site itself, alleging that the presence of religious symbols and artifacts was troubling and overshadowed what was supposed to be a celebratory occasion.

An appeals court ruled that holding the ceremonies there was unconstitutional, as it violated the separation of church and state principle. The court declined to hear the case, effectively affirming the lower court’s decision.

Scalia said that Elmbrook School District v. Doe had been decided using the “endorsement test” and not the “coercion test” used in the court’s recent ruling in Town of Greece v. Galloway, where the court ruled that sectarian prayers were allowed at government meetings.

READ: Supreme Court approves sectarian prayer at public meetings

Scalia was characteristically witty or brash (depending on your predilections) in his dissent. Students and families being offended was irrelevant, said Scalia. He said he was frequently offended by certain types of music:

“There are—many, perhaps—who are offended by public displays of religion. Religion, they believe, is a personal matter; if it must be given external manifestation, that should not occur in public places where others may be offended. I can understand that attitude: It parallels my own toward the playing in public of rock music or Stravinsky. And I too am especially annoyed when the intrusion upon my inner peace occurs while I am part of a captive audience, as on a municipal bus or in the waiting room of a public agency.”

But in the Town of Greece decision, said Scalia, the court ruled that being offended does not mean that one is being coerced. “It is perhaps the job of school officials to prevent hurt dissenting feelings at school events,” Scalia wrote, “But that is decidedly not the job of the Constitution.”

That was the essence of Scalia’s jurisprudence that he advocated throughout his tenure. He had a clear, unwavering view that the words of the Constitution were the end-all and be-all. And the words of the First Amendment, according to Scalia, meant that government could not establish a national church, but it did not mean that government should be secular.

“God has been very good to us,” Scalia told the high school last month. “That we won the revolution was extraordinary. The Battle of Midway was extraordinary. I think one of the reasons God has been good to us is that we have done him honor.”

(Tobin Grant blogs for RNS at Corner of Church and State, a data-driven conversation on religion and politics. He is a political science professor at Southern Illinois University and associate editor of the Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. Daniel Bennett (@bennettdaniel) researches the conservative legal movement. He is a professor of political science at Eastern Kentucky University)