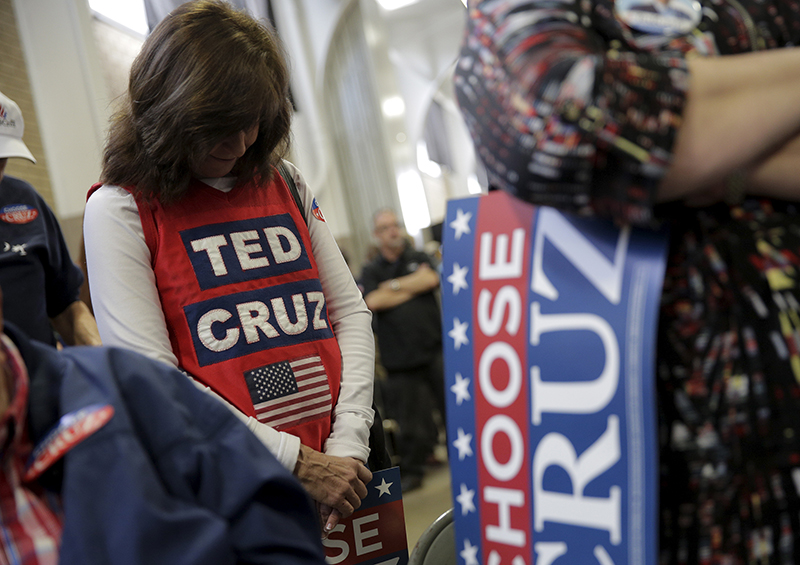

Supporters of Republican presidential candidate Ted Cruz pray at the start of a campaign event in Columbia, S.C., on Feb. 16, 2016. Photo courtesy of REUTERS/Joshua Roberts

*Editors: This photo may only be republished with RNS-FARNSLEY-COLUMN, originally transmitted on Feb. 23, 2016.

(RNS) Many self-professed evangelical Christians are voting for Donald Trump. Trump is not an evangelical Christian, and neither his personal background nor his policy proposals seem like a very good fit for religious conservatives.

There is a very conservative evangelical Christian running on the Republican side — Texas Sen. Ted Cruz — so it seems like evangelicals should be voting for him.

Something is askew, and political analysts are starting to notice.

Some recent analysis is leaning in the right direction, but I would like to give it a shove.

The National Review ran a post using church attendance as a way to think about the difference between the very large set of people, especially in the Southeast, who call themselves “evangelical” and the much smaller subset of these who attend church regularly and are likely to use their faith as a guide to voting.

It suggested Cruz might be the choice of the smaller group, but not necessarily the larger one.

This is on the right track, but the underlying analytical problem runs much deeper. All of us — pundits, academics, casual observers — develop narratives about religion’s influence that are much too tidy. We see a relationship — in this case between evangelicals and certain political issues — and then infer much, much more from it than the facts will allow.

READ: Trump, Cruz popularity represents two very different Christian failures (COMMENTARY)

The term “evangelical” is an excellent case in point. In the very broadest sense, this refers to anyone with a personal relationship to Jesus. The Pew Research Center says 30 percent of Americans identify as evangelicals or as born again, which is about 96 million people. (For comparison, 127 million people voted in the last presidential election.)

This is roughly the same percentage of Americans who believe the Bible is the Word of God and should be taken literally. The two groups overlap, though they are not identical.

Obviously, not all of those 96 million people are part of the self-conscious, politically mobilized subculture sometimes called “evangelicalism.” That subculture has institutions: magazines (Christianity Today), books (“The Purpose Driven Life”) and special-purpose organizations (Focus on the Family). This subculture is an integral part of American life but is much, much smaller than 96 million people.

Predicting the political action of this highly institutionalized group would be difficult enough; using the group to infer the actions of tens of millions more who call themselves “evangelical” is plainly foolhardy.

READ: Noah’s Ark park may ease religious requirements for workers

Evangelical pollster George Barna makes this point very effectively with his nine-point list of beliefs and practices that define evangelicals. By Barna’s more rigorous definition, the percentage of evangelicals in America is more like 9 or 10 percent. The number of “movement evangelicals” is much smaller than the number of people who accept the evangelical designation.

I drew a similar distinction in a 2006 article in Christianity Today. I had been interviewing flea market dealers in Indiana and found two interesting, related facts: The dealers believe the Bible to be literally true, and virtually none of them ever read it.

Nationally, political analysts were starting to construct wild-eyed scenarios along these lines: “The biblically conservative Christian right vote is already X percent, but at least half of biblically conservative Christians are not yet politically mobilized. If they ever are, they could reach Y percent.”

I pointed out that Y percent was never going to happen. The fact people believed the Bible to be literally true did not mean they were ripe for political mobilization because mobilization is about resources, money and ideas, and these flow through institutional channels. My flea market dealers were not part of that world and were never going to be. They were believers, to be sure, but their beliefs did not translate into action.

In my 2012 book “Flea Market Jesus,” I pushed the point further. The flea market dealers did not attend church, but the differences between them and movement evangelicals were much broader. The dealers could not name any famous television preachers, like Charles Stanley or James Dobson; had never heard of the “Left Behind” book series; and did not really care about abortion or gay marriage. As I said then, “The flea market literalists are not prone to political mobilization, but if it ever happens, it will be because a populist has pricked their fears, not because a religious conservative has stoked their zeal.”

What I did not foresee, what nobody foresaw, was that this group might be activated without the fundraising and institution-building of traditional political mobilization if a candidate could manipulate the media enough to create his own story.

READ: ‘Risen’ movie raises old Hollywood trope — unbeliever meets Jesus

That’s not to say everyone in the evangelical subculture is supporting Cruz, while the less-committed, everyday evangelicals are supporting Trump. Jerry Falwell Jr. and the pastor of First Baptist Church in Dallas have made public appearances with Trump that border on endorsement.

But it is to say we all need to admit we often try to assume or infer way, way too much from religious identification.

Seen from a wide enough angle, religious affiliation is a pretty good marker. People who attend church regularly are, for instance, more likely to vote Republican. That level of prediction holds up.

But from a tighter angle, trying to parse differences among Protestants who profess a personal relationship with Jesus, we need to admit our predictions are not nearly as good.

Arthur E. Farnsley II is professor of religious studies at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis and author of “Flea Market Jesus.“ Photo courtesy of Arthur E. Farnsley

A lot of people say the Bible is literally true. A lot of people say they are “evangelical.” But it is a mistake of the first order to jump to the conclusion that all of these people are like members of the 700 Club, Moral Majority or Focus on the Family.

Religion is just one lens people use to view the world; for many, it is not the most important lens. It is a mistake to assume 96 million people who call themselves evangelicals all want the same thing from their political leaders or their government. Here as elsewhere, if our stories seem too tidy, they are probably wrong.

(Arthur E. Farnsley II is research professor of religious studies at Indiana University-Purdue University Indiana, director of the IU Center for Civic Literacy and associate director of the Center for the Study of Religion and American Culture)