(RNS) It is not easy to be a respected member of the art-world intelligentsia and take religion seriously.

“Religion and modern art continue to be typecast as mortal enemies,” writes Aaron Rosen.

But the very context in which he makes this statement suggests that a truce may be in the works. Rosen is the author of the copiously illustrated book “Art + Religion in the 21st Century,” which illustrates his belief that there is “a tremendous potential for reciprocity” between the two.

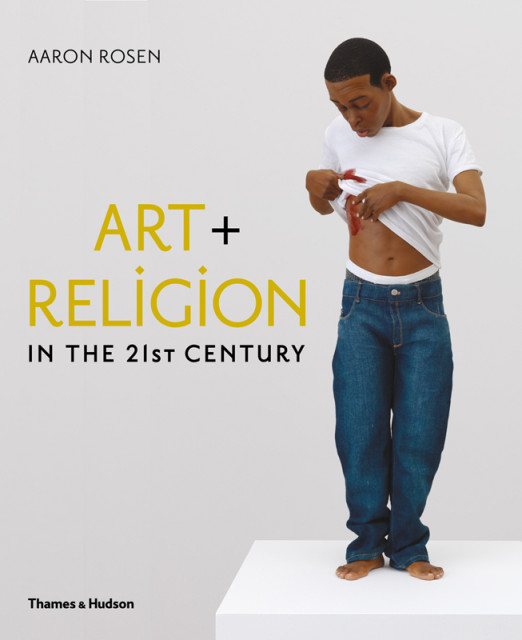

“Art + Religion in the 21st Century” by Aaron Rosen. Book cover photo courtesy of Thames & Hudson

And his may be the voice of the future.

Many of the currents in 20th-century culture made it hard to imagine the phrase “contemporary religious high art.”

Most artists hold religion at arm’s length. Heroic images of the Holy Family and the Catholic saints that were staples of the art of faith fell out of fashion; meanwhile, institutional Catholicism, wary of stirring controversy within its ranks, moved away from museum-grade art, and evangelical Protestant art had a not-ready-for-prime-time look.

READ: Can the greatest religious painter of the 20th century make a comeback?

But Rosen, a Maine native and a lecturer on sacred traditions and the arts at King’s College London, is at the forefront of a small but growing cadre of scholars who think it is time to reassess.

His book is a spirited exploration of the ways contemporary art and religion are exploiting what he calls “a tremendous potential for reciprocity.” The 200 images in “Art + Religion” run the gamut from the cartoonist R. Crumb’s version of Genesis to the painter Makoto Fujimura’s abstract illustrations for the King James Bible.

Aaron Rosen in front of G. Roland Biermann’s sculpture “Stations” (2016), produced for Rosen’s “Stations of the Cross” exhibition. Image courtesy of Anne Schwarz Photography

Rosen recently curated an ambitious “Stations of the Cross: Art and Passion” exhibition that includes artworks all over London by Christian, Jewish, Muslim and atheist artists. He is also celebrating the publication of a scholarly book on Manhattan’s St. Peter’s Lutheran Church, home to famous Louise Nevelson sculptures. This Q&A has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: Your cover image is a 2-foot-high, super-realist sculpture of a black teen, staring uncomprehendingly at blood seeping through his T-shirt from a wound in his side, evoking Christ. If Black Lives Matter were looking for a faith-based emblem, this could be it.

A: It refers back to Caravaggio’s “The Incredulity of St. Thomas.” It’s by an Australian artist, Ron Mueck, who was in London in 2009 when there was heavy coverage of knifings. I worried we might be seen as appropriating the very different tragedies in the States. But now I think it’s fitting. The boy’s incredulity, like the original Doubting Thomas story, asks, “What does it take to make us believe?” We’ve seen abundant visual testimony of shootings and abuses by authorities. Maybe this work helps underline the very real martyring of black people in America.

From “Art + Religion in the 21st Century,” by Aaron Rosen — Adi Nes, Untitled, 1999. Color photographic print. Photo courtesy of Jack Shainman Gallery, New York, and Sommer Contemporary Art, Tel‐Aviv

Q: You write, “When you enter the world of art, you are, like it or not, entering the realm of religion.”

A: Step into most Western museums, and you feel the presence of Christian cultural history. But religion of some sort is present in a lot of art. In Australian aboriginal art, you can’t tell where it ends and the art begins. In the West, boundaries are often erected, but it’s more blurred than people admit. The theologian Paul Tillich said artists want to ask questions of ultimate meaning, and so do religious people.

Q: How did you come to write the book?

A: I teach a class on art and religion, and the available books seemed stuck in the 1980s culture wars, that religion-versus-art cartoon where the winners were politicians and publicity-hungry art dealers. The real losers were religion and art.

Q: Are we past that?

A: Well, perhaps not. And we’re in an election cycle. But this is a moment of tremendous opportunity. Artists on the ground are engaging with religion in both more sophisticated and more subtle ways than we expect.

From “Art + Religion in the 21st Century,” by Aaron Rosen — Mark Wallinger’s “Ecce Homo,” 1999. Sculpture, white marbleized resin and gold-plated barbed wire, life-size. Photo courtesy of Hauser & Wirth. © Mark Wallinger

Q: Museums have historically perpetuated the either/or distortion by refusing to recognize the religious power of religious art, beyond its art-historical importance.

A: I think that may be shifting. In the U.K. there were three blockbuster shows at the National Gallery featuring altarpieces and other religious works arranged in ways the curators hoped would recapture some of their ritual and devotional power — without implying viewers needed to convert. They were huge hits.

Q: You also describe artists utilizing houses of worship as showcases, from Bill Viola’s video altarpiece, “Martyrs,” in St. Paul’s Cathedral in London to a German graffiti artist who spray-painted the interior of a church in the town of Goldscheuer.

A: It’s mutual need as much as shared theology. Many churches can’t afford to decorate themselves properly, and many artists are desperate for a place to show work where people will spend serious time looking at it. In a few cases, though, the art has actually revived dwindling congregations and drawn in different ages, which happened with the “graffiti church.” St. Paul’s has plenty of viewers, but Viola has helped draw in young people, especially.

Q: Yet many artists fear being “ghettoized” as Christian or Jewish or Muslim artists.

A: Museums, and especially galleries, are far more comfortable talking postmodern theory than Jesus or Abraham. Artists may be privately religious, take inspiration from art of the religious past, create work for churches and do a lot of seemingly religious things. But I’d have to say that career-wise, anyone expecting art-world success who describes himself as a “Christian artist” is usually either very brave or very stupid.

From “Art + Religion in the 21st Century,” by Aaron Rosen — Nazif Topcuoglu’s “Is It for Real?,” 2006 C-print. Photo courtesy of Green Art Gallery, Dubai. © Nazif Topçuoglu

Q: On the flip side, you include images where a religious image is appropriated for ambiguous purposes, as when Adi Nes populates Leonardo da Vinci’s “Last Supper” with a table of Israeli soldiers; or the high-glitz photographer David LaChapelle creates a “Pieta” with an actor made up to look like Christ cradling a Michael Jackson look-alike, scrambling gender and identity. Should it bother us when we can’t figure out whether the art is offering a prayer or a smirk?

A: I think mixed messages can actually be a good thing. LaChapelle did a whole series called “American Jesus” that I think smuggles in religious significance under what you could call the veil of irony. When certain people rule out the idea that the work involves true feeling, and others dismiss it out of hand as blasphemous, both miss out. My advice is: Start from the assumption that a work of art could have significance and meaning for your life, and go from there. Then, if you still choose to condemn or ignore it, fine. But start with the premise that it’s meaningful. Have faith in art.

(David Van Biema is a correspondent for RNS)