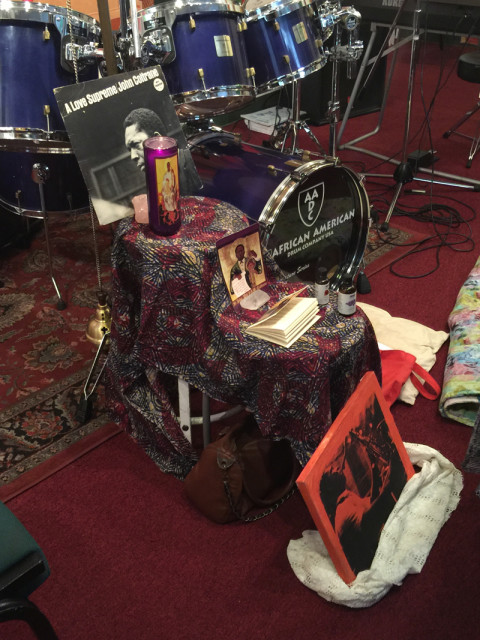

The altar of St. John Coltrane Church is set with a drum kit, a keyboard, a saxophone and, most importantly, a much-loved vinyl rendering of a jazz classic, complete with liner notes. Religion News Service photo by Kimberly Winston

SAN FRANCISCO (RNS) The altar is set with a drum kit, a keyboard, a saxophone and, most importantly, a much-loved vinyl rendering of a jazz classic, complete with liner notes.

When this church and its 70 members are forced to leave their storefront location at the end of next month, they will pack those instruments as lovingly as they will the shiny brass tabernacle that holds the Eucharist, the brass cross and the scarlet and gold icons that grace all the walls.

This is St. John Coltrane Church, a 48-year-old institution in this city’s Fillmore District, just south of swankier Pacific Heights. Sunday Masses are built on a live performance of “A Love Supreme,” a 33-minute opus that saxophonist Coltrane wrote to express the awesomeness of God.

“St. John Coltrane referred to this music as being an expression of higher ideals,” said the Rev. Wanika Stephens, who played the electric bass guitar during the Palm Sunday Mass while a standing-room-only crowd waved its greenery and bopped to the beat.

“The music has a power to unify us, to bring us together,” she said. “Because of that, he felt that a brotherhood was there in the music and if you had that brotherhood you would have no more poverty, no more war. The music has that power.”

The Rev. Wanika Stephens plays the electric bass guitar during the Palm Sunday Mass at St. John Coltrane Church while a standing-room-only crowd waved its greenery and bopped to the beat. Religion News Service photo by Kimberly Winston

That belief is reflected in an oversized icon of the musician that dominates one wall of the church. His penetrating eyes stare straight out, his left hand clasping a saxophone spewing flames, his right hand clutching a banner that reads, “Let us sing all songs to God to whom all praise is due.”

But where the music will play next, and for how long, is unclear. The church is the most recent victim of gentrification in the Fillmore, once home to numerous jazz clubs and late-night bars that are now making way for condos and coffeehouses. As they are in other parts of this expensive city, lower-income residents, many of them African-American and Latino, are being priced out.

Church officials say the landlord stopped accepting their monthly $1,600 rent checks two years ago and attempted eviction last September. That was averted with a petition of 4,000 signatures, way more than the church’s worldwide membership of 700. Now, landlord Floyd Trammell — himself a pastor at another church — has agreed to withdraw eviction proceedings if the church will peacefully vacate by the end of April.

Trammell has repeatedly declined to discuss the eviction, issuing a statement that reads, in part, that he “operates in the same ruthless economy that has engulfed the entire Fillmore District.”

The church’s final service will take place April 24. After that, church officials do not know where they will alight next but say they would like to stay in the neighborhood where they have so many roots. They have started a fundraising campaign to cover moving costs.

“The ruling principle of God’s love is a love supreme,” said the Rev. Franzo W. King, the church’s founder, archbishop and sax player, as he welcomed Palm Sunday’s gathered — about 80 people, some from the neighborhood and some from as far away as Germany, Spain and Australia.

“The saxophone is like a surgical instrument that is capable of cutting away fear, of cutting away evil,” he continued, his long, thin frame upright in clerical black with a white collar framed by a gold chain necklace. “And John Coltrane is the supreme surgeon.”

King and his wife, Mother Marina King, started the church after attending a Coltrane show in 1965. As Nicholas Baham III recounts it in his book “The Coltrane Church: Apostles of Sound, Agents of Social Justice,” the pair were out for fun, but had a spiritual experience.

The Rev. Marlee-I Mystic sings vocals, left, while Landres King plays drums and Franzo King III plays the keyboard during the “A Love Supreme” Mass at the St. John Coltrane Church in San Francisco. Religion News Service photo by Kimberly Winston

“They had what they call a ‘sound baptism,'” Baham, a professor of ethnic studies at California State University, East Bay, said in a telephone interview. “They saw the Holy Ghost walk out on stage with John Coltrane and the movement started from there.”

The Kings started the church in their San Francisco living room after Coltrane’s death in 1967. Three daughters and a son are all ordained clergy in the church and play instruments or sing in the liturgy. Grandchildren play the drums, the keyboard and dot the chairs.

Daniel Landry Muhammad plays the drum at St. John Coltrane Church, which faces eviction from its home in San Francisco. Religion News Service photo by Kimberly Winston

While church members revere Coltrane, they do not worship him. And while other churches have incorporated jazz into their worship services, the Church of St. John Coltrane is different in that its members see the music as a vehicle to “Coltrane consciousness,” a higher state of mind achieved through the music and through living Coltrane’s anti-poverty, anti-war, social justice beliefs.

“They use the music as a meditation and they glean everything they can about living from Coltrane’s life and writing and music,” Baham said.

The church aligned itself with the African Orthodox Church, a denomination with Episcopal roots, in 1981. It moved from the King living room to other places in the Fillmore. It has been in its current location for 10 years.

And if it departs the Fillmore, something truly unique to San Francisco and African-American life will be lost, Baham said.

“The community that remains is going to lose a very important social justice player that has fought environmental racism, economic racism,” Baham said. “And let’s not forget the new pastor is a woman, which is very progressive for an African-American church in this country.”

An icon of jazz saxman John Coltrane hangs in a church that bears his name, where he is considered a saint. Religion News Service photo by Kimberly Winston

Stephens — that woman pastor — said there is an “energy of love, of truth and of light that is compelling” the church forward.

“It is really larger than myself or any of the clergy there, but it is certainly something we all feel and we are all a part of it,” she said. “It is a labor born out of love and it is a service of love that we hunger for.”

Before the Palm Sunday service, clergy, church members and other supporters took Coltrane’s music to the sidewalk to protest the eviction. With King on sax and his daughter, the Rev. Marlee-I Mystic, on the tambourine and vocals, they sang and played a call-and-response some passers-by took up.

“San Francisco is moving away from the past,” said Daniel Landry Muhammad during a break from his drum adorned with the face of Che Guevara, the Marxist revolutionary. “We have to resist. We are coming back.”

(Kimberly Winston is an RNS national reporter)

Religion News Service video by Kimberly Winston