NEW YORK (RNS) — Two days before Election Day 2020, Pastor Justin Adour of Redeemer East Harlem Church had a message he knew his congregation didn’t want to hear.

Though it “might make your stomach turn a little bit,” he told both his socially distanced live listeners and viewers watching online, a “Democrat Christian” has more in common with conservative Christians — even “a staunch Trump-supporting Republican” — than with fellow Democrats who are not Christians. “And vice versa,” he added.

Adour’s church, part of a network founded by popular Presbyterian Church in America pastor and theologian Tim Keller, is as diverse as its gentrifying neighborhood. Adour said his 100 to 150 members are Black, Asian, Hispanic and white.

And he knows he has supporters of both President Donald Trump and President-elect Joe Biden sitting in his pews.

Pastors in the American church are used to dealing with division. “Our churches have always been segregated, because Christians — primarily white Christians — always held their whiteness in greater esteem than Christ,” he told Religion News Service before Election Day.

“There is a lot of unifying things about the gospel,” Adour insisted.

Justin Adour preaches on Sunday, November 8 at Redeemer Presbyterian East Harlem. Video screen grab, Redeemer East Harlem YouTube.

Christian leaders across the country have been sounding that theme in the aftermath of the election, as the president and some of his allies have disputed the call made by The Associated Press and other major media outlets projecting that Biden would be the 46th president of the United States.

After an election year in which Trump hewed closely to a base thickly populated by evangelical Christians while enduring fierce opposition from a revived religious left, these pastors and other Christian leaders are urging followers of all political convictions to find common cause in their faith.

“A divided country needs a united church,” tweeted Ed Stetzer, professor and dean at Wheaton College in suburban Chicago, where he is executive director of the Wheaton College Billy Graham Center.

Unlike some evangelical leaders who suggested in the runup to the election that Christians — especially white Christians — had no choice but to vote Republican, J.D. Greear, president of the Southern Baptist Convention and pastor of the Summit Church in Durham, North Carolina, said that Christians shouldn’t neatly fit into either political party.

Nor should they engage conversations about politics in the same way as others, Greear said in a podcast episode recorded the day after the election.

“The political discourse in our country trains us to assume the worst about everybody else’s motives even as we demand that they assume the best about ours. … I just think in the church we need to be better,” he said.

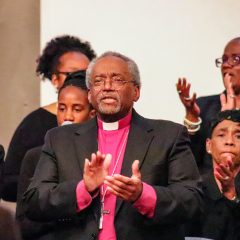

Bishop Michael Curry, presiding bishop of the Episcopal Church, told those gathered for an interfaith prayer service on Sunday (Nov. 1): “We must heal our country. I think some of that is the great work that is before us as a country, and certainly before the church and people of faith.”

The service, livestreamed from Washington National Cathedral in the nation’s capital and titled “Holding on to Hope: A National Service for Healing and Wholeness,” started with confession, grief and lament.

“You can’t just jump to hope,” Curry said. “There’s a process you have to go through. There are no shortcuts to it.”

The presiding bishop, in an interview with RNS, said healing won’t come by of prayer alone, but by people getting to know each other across divides.

“You’ve got to pass laws. You’ve got to change the policy,” Curry said. “But the truth is: Changed laws and changed policies don’t change hearts, and until you change hearts, you don’t change everything. You’ve got to take a holistic approach.”

The Rev. Jes Kast has been doing that work in her own little corner of central Pennsylvania, where she pastors Faith United Church of Christ in State College.

Just after the 2016 election, Kast moved to State College from New York City, where she had lived for nearly a decade. She felt called to Faith, she said. She also felt called to move to a “purple state,” where she hoped she could speak across divides.

“I don’t underestimate that just being an out, married woman in this area is like a testimony in itself and profoundly Christian,” said Kast, who identifies as lesbian and grew up evangelical in Michigan.

Living in central Pennsylvania, the pastor has learned how to pickle and garden and why hunting is important to her rural neighbors. She has showed up on a farm wearing heels. It’s important to her because the people are important to her.

Her neighbors “are changing because they get to know me and I’m choosing to be vulnerable, and I’m changing because I understand, oh, this is what’s going on with farmers in Pennsylvania. This is how gun conversation is nuanced differently for rural folks,” she said.

But, Kast said, healing and unity are two different things.

After four years of a president elected by a minority that included his impeachment and massive demonstrations for racial justice — some of them outside a besieged White House — some Christian leaders find the idea of unity dubious.

“Miss me with the ‘unity’ and ‘healing’ platitudes,” tweeted Austin Channing Brown, author of the bestselling book “I’m Still Here: Black Dignity in a World Made for Whiteness.”

She shared an image with the words, “Im wholly uninterested in a conversation about unity thats not rooted in the unrelenting pursuit of racial justice.”

Writer and speaker Danté Stewart told RNS he isn’t sure unity is possible. Stewart called the idea that this generation finally will be the one to solve white supremacy or redeem an America that he sees as committed to imperialism and oppression “historical arrogance.”

Stewart, who is Black, believes white Christians need to do the work of confronting their racism, and without that, unity is impossible.

But, that would take a “miracle,” Stewart said, involving “everyday ordinary people committing to better policy, better practice and being better people than what they’ve been in the past.”

Curry, though, said he doesn’t think it is naively optimistic to believe the church or the country has the ability to heal and move forward together.

Episcopal Church Presiding Bishop Michael Curry claps at a revival at Harvest Assembly Baptist Church in Alexandria, Virginia, on March 6, 2019. RNS photo by Adelle M. Banks

As the first Black presiding bishop of the Episcopal Church and a descendant of enslaved people, he said, “I’m a product of that tradition that has learned that there is progress and there are steps forward and then there’s a pushback.”

Still, he said, it’s important to keep moving forward.

“I believe it is possible for us to be instruments of healing in this culture, and I refuse to give up,” Curry said.

In East Harlem, Adour said what it will take is listening — and trying to help others listen, too.

“It’s very easy to put someone in a box as soon as they start talking about an issue,” he said.

“So often we dishonor Christ by trusting politicians or ideologies to idolatrous degrees. Or we refuse to love brothers and sisters in Christ across these dividing lines, instead desiring to demonize them or marginalize them or ignore or patronize them,” he said.