(RNS) High school kids can join the Fellowship of Christian Athletes, the Jewish Student Union, the Muslim Students Association and, in some schools, a Hindu or a Buddhist club.

Now they can join the young atheists club, too.

In another sign of the emergence of nonbelievers in American society, the Secular Student Alliance, a national organization of more than 300 college-based clubs for atheists, humanists, agnostics and other “freethinkers,” is helping to establish clubs for high school students to hang out with other teens who share their skepticism about the supernatural.

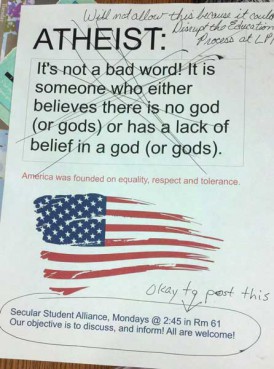

(Houston, Tex) This poster was rejected by a La Porte High School administrator. He told students their club, for nontheistic students – could not use the word “atheist” in their posters because “it could disrupt the education process” at their high school.

“I am hoping that atheist students having their clubs and religious students having their clubs will promote dialogue,” said JT Eberhard, director of SSA’s high school program. “I also hope it will let the atheist students know that you can be an atheist and its okay. You are still a good person. We want to say: Here is a place where you can feel that.”

There were about a dozen such clubs at the beginning of the 2011-2012 academic school year, a figure that rose to 39 in 17 states by summer break. The clubs are student-led, with SSA providing information and guidance only upon a student’s request.

Some clubs are in states with high levels of “nones” — people who claim no religious affiliation — such as New York, Washington and California. But some are in the buckle of the Bible Belt: North Carolina, Alabama, Louisiana and Texas all have at least one high school with a club for atheists.

And more are forming. Students at 73 different high schools have requested “starter kits” since January of this year, according to SSA.

Eberhard attributes the growing interest in atheism among high school students to several factors, including disenchantment with organized religion amid recent scandals and the rise of the Internet, which gives young doubters a safe forum to ask questions.

Two recent studies show religious doubt rising among “Millennials,” those Americans born after 1980. In April, the Pew Forum for Religion and Public Life reported 68 percent of Millennials “never doubt the existence of God,” down 15 points since 2007. And in June, the Public Religion Research Institute found that one in four Millennials report no religious affiliation.

Still, launching an atheist club is not always a smooth process. Some sail through a school’s approval process once they have met the school’s criteria, which usually means obtaining a faculty sponsor and demonstrating student interest.

Trevor Lynn, 17, said he faced no administrative resistance when he started an atheist club at his Eureka, Calif., high school in 2010.

“The administration of our school really prides itself on being able to have a club for everybody,” Lynn said. “They saw no reason to stop us.”

Now, his group — about seven members — meets to discuss philosophy and ethics and stage special events. In September, the club will host joint lectures on evolution and creationism by a prominent freethought author and a local pastor.

“I think it is important, especially in high school where people are coming into their own beliefs, that we have a space where people can feel kind of secure in their nonbelief and have a meeting where they know there are other people like them,” Lynn said. “That is the big reason I started the club.”

Others have a harder time.

Administrators at Melbourne High School in Melbourne, Fla. rejected an atheist club twice on the grounds it was “too controversial.” Students at another Florida high school were told by administrators that no religious clubs were permitted — despite the existence of a school Christian club. And at Houston’s La Porte High School, the principal denied students the use of the word “atheist” because “it could disrupt the educational process.”

In these cases, Eberhard usually calls administrators and reminds them that the Equal Access Act gives the the students the right to form a club.

That law says if a federally funded secondary school permits even one extracurricular club, it must permit them all, providing “equal access” to school property. It was passed in 1984 with the support of religious groups who wanted to establish after-school Bible clubs.

“The irony is that same act allows secular students a place in the classroom for their club,” Eberhard said.

Others are more measured in their support. Dave Rahn, chief ministry officer for Youth For Christ/USA, said a pluralistic society means his group, which oversees 1,100 middle and high school clubs, “will often co-exist on campus with groups promoting worldviews with which we simply disagree.”

“When we faithfully communicate the truth of the gospel we expect it will be fruitful among young people, no matter what other ideas compete for their allegiance,” he said.

Steve Gerali, dean of the theology department at Grand Canyon University and an expert on ministry to youth, said he is concerned that some administrators favor nonreligious clubs over religious ones.

“My perception is that an atheistic club is a little bit more welcomed than a Christian club,” he said. “I think administrators need to understand that to speak about no God is

similar to speaking about a God. So it is, in fact, a religion even though it is anti-religion.”

Not so, said Robert-Cole Evans, 16, who started an atheist club at his Spring Branch, Texas, high school. His group includes Christians, who, like many members of his club, are interested in discussing matters of belief.

At a recent fundraiser, Evans said, a woman approached him and asked if he was a Christian. When he said no, he was an atheist, she said that was “OK” because “it was good to see kids with energy and passion for what they care about.”

“You can’t say anyone is amoral or evil until you have talked with them,” Evans said.