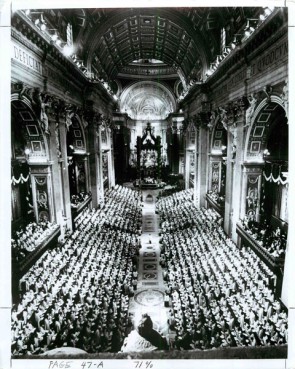

(RNS) Fifty years ago on Thursday (Oct. 11), hundreds of elaborately robed leaders strode into St. Peter's Basilica in a massive display of solemn ecclesiastical pomp. It signaled the start of a historic three-year assembly that would change the way members of the world’s largest Christian denomination viewed themselves, their church and the rest of the world.

Vatican City — Prelates and religious dignitaries from around the world fill St. Peter's Basilica as a concelebrated Mass opens the Second Vatican Council on Oct. 11, 1962.

It was the first day of the Second Vatican Council, more popularly known as Vatican II, which was designed to assess the church’s role in a rapidly changing world. Leading the prelates was Pope John XXIII, who said frequently that he convened the council because he thought it was time to open the windows and let in some fresh air.

For many Catholics, the air came in at gale force.

As a result of Vatican II, priests started celebrating Mass in the language of the countries in which they lived, and they faced the congregation, not only to be heard and seen but also to signal to worshippers that they were being included because they were a vital component of the service.

“It called for people not to have passive participation but active participation,” said New Orleans Archbishop Gregory Aymond, who chairs the Committee on Divine Worship for the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. “Prayer is not supposed to be a performance. We’re supposed to be actively participating.”

The changes didn’t stop when Mass ended. As time went by, many nuns shucked their voluminous habits in favor of clothes similar to those worn by the people they served. And men and women in religious orders started taking on causes, even risking arrest, when they spoke out in favor of civil rights and workers’ rights and against the war in Vietnam.

Such changes represented an about-face from the church’s defensive approach to the world before Vatican II, said Christopher Baglow, a theology professor at Notre Dame Seminary in New Orleans.

“It wasn’t that the church wasn’t committed to human dignity before Vatican II,” he said. “With Vatican II, the church began to look closely at the ways with which modern thinkers tended to promote human dignity and showed how they and the Gospels are complementary.”

With Vatican II, the Catholic Church sent out the message that it was part of the modern world, said Thomas Ryan, director of the Loyola Institute for Ministry. “Not against, not above, not apart, but in the modern world,” he said. “The church sought to engage, not condemn.”

The council documents say there must be a conversation between the church and the world, Aymond said. “The church, by its teaching and by its discipleship, has something to say to the world. At the same time, the world is saying something to the church.”

“We can’t just say we’re not going to be involved in these conversations,” he said. “As the church, we have to be in conversation with others who agree and disagree with us.”

This shift included the Catholic Church’s attitude toward other religions. Before Vatican II, Catholics weren’t supposed to visit other denominations’ houses of worship. “Catholics looked down on other religions and thought of them as condemned to hell,” Ryan said.

But one document from the council acknowledged that these disparate faiths had a common belief in God, said Ryan, who described it as nothing less than “a revolutionary approach.”

Perhaps the biggest of these changes came in the church’s approach to Judaism. Before Vatican II, Jews were stigmatized as the people who killed Jesus Christ. That changed with the council, when the Catholic Church acknowledged its Jewish roots and Jews’ covenant with God, Ryan said.

“It had the effect that the sun has when it comes up and interrupts the night,” said Rabbi Edward Cohn of New Orleans' Temple Sinai, whose best friend as a child had to get permission from the archbishop to attend Cohn's bar mitzvah. “It was no less dramatic than that. It provided an entirely new day. It changed everything.”

Not all the changes brought about by Vatican II have been welcomed, and many would say there haven’t been enough changes regarding the status of women. This spring, the Vatican orthodoxy watchdog launched a full-scale overhaul of the largest umbrella group of American nuns, accusing the group of taking positions that undermine church teaching and promoting several “radical feminist themes” that are incompatible with Catholic teachings.

Although Vatican II was a catalyst for a great deal of change, it didn’t happen in a bubble, Aymond said. The 1960s was a decade of change, with protests against racism, war, sexual behavior, the status quo and authority in general.

“If that’s going on in the world and in society, that’s bound to affect the church because we’re both a divine and a human institution,” Aymond said.

“Vatican II isn’t about replacing what the church is,” said Baglow, the theologian at Notre Dame Seminary. “It’s about helping it be more vitally what God intended it to be in the first place.”

(John Pope writes for The Times-Picayune in New Orleans.)