(RNS) When the Vatican last month announced a doctrinal crackdown on the leadership organization representing most of the 57,000 nuns in the U.S., the sisters said they were “stunned” by the move. Many American Catholics, meanwhile, were angry at what they saw as Rome bullying women whose lives of service have endeared them to the public.

Vatican watchers also were perplexed since a broader, parallel investigation of women’s religious orders in the U.S. was resolved amicably after an initial clash. That seemed to augur a more diplomatic approach by the Vatican to concerns that American nuns were not sufficiently orthodox.

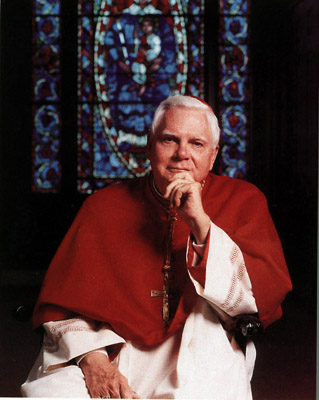

Now it turns out that conservative American churchmen living in Rome — including disgraced former Boston Cardinal Bernard Law — were key players in pushing the hostile takeover of the Leadership Conference of Women Religious, or LCWR, which they have long viewed with suspicion for emphasizing social justice work over loyalty to the hierarchy and issues like abortion and gay marriage.

Vatican observers in Rome and church sources in the U.S. say Law was “the person in Rome most forcefully supporting” the LCWR investigation, as Rome correspondent Robert Mickens wrote in The Tablet, a London-based Catholic weekly. Law was the “prime instigator,” in the words of one American churchman, of the investigation that began in 2009 and ended in 2011. The actual crackdown was only launched in April.

Law was joined by a former archbishop of St. Louis, Cardinal Raymond Burke, who was named to a top Vatican judicial post in 2008 – a move that was seen as a case of being “kicked upstairs” because Burke’s hard-line views made him so controversial in the U.S. Also reportedly backing the probe was Cardinal James Stafford, a former Denver archbishop who has held jobs in the Roman curia since 1996.

The investigation itself was conducted by Cardinal William Levada, a former archbishop of San Francisco who succeeded Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger as head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, the Vatican’s powerful doctrinal watchdog, when Ratzinger was elected Pope Benedict XVI in 2005.

The fact that prelates like Burke and Law, who was given a Roman refuge in 2002 after the sexual abuse scandal exploded in Boston, played such a key role in the investigation of the American women has been like salt in the wound for those who support the nuns.

“American Catholics have not forgotten how long it took bishops to wake up to the sexual-abuse crisis they created. And now they see that the Vatican took just three years to determine that it had no other option but to put 80 percent of U.S. nuns — whose average age is 74 — into receivership, an effort led in part by Cardinal Bernard Law,” Grant Gallicho, an associate editor of Commonweal, a liberal Catholic periodical, wrote on the magazine’s blog.

“That decision has unified a good deal of Catholics all right — against Rome,” Gallicho concluded.

The decision also shone some light on the Byzantine maneuvering that can characterize Vatican politics – and hurt the Vatican’s public relations.

A case in point: in 2008, a year before Levada’s office started investigating the LCWR, the Vatican department that oversees nuns and brothers worldwide began a broad investigation, or “visitation,” of all women’s religious orders in the U.S. That was prompted as usual by complaints that the orders were too liberal and so had few recruits.

The nuns pushed back against what was seen as a heavy Roman hand, and in 2010 an American, Archbishop William Tobin, was appointed to head the probe for the Vatican. A few months later, a well-regarded Brazilian, Cardinal Joao Braz de Aviz, was promoted to lead the curial department that oversees religious orders.

Tobin and Braz de Aviz took a much more conciliatory approach, and the visitation concluded without fireworks. In addition, Sister Nicla Spezzati joined the two men at the religious orders office. Spezzati does not regularly wear a habit – the kind of thing that galls conservative churchmen about so many sisters in the U.S.

“This changing of the guard at the top of the congregation for religious was not at all to the liking of the cardinals from the United States residing in Rome at the time,” wrote Sandro Magister, a longtime Italian Vaticanologist.

The Americans in Rome moved to ensure that Levada’s rival investigation of the LCWR would follow a different path, according to church experts and insiders. The result was that one probe ended with an accommodation and another seemed like an ambush. It was no surprise which one generated more media coverage.

Not that it had to wind up that way. John Allen, Vatican expert for the National Catholic Reporter, reported that a senior Vatican diplomat warned his colleagues earlier this year that launching a crackdown from Rome now would play into the “war on women” theme that has been associated with the American hierarchy’s campaign against the Obama administration’s contraception coverage mandate.

The response from officials in Levada’s office, Allen wrote, was that such concerns were “exaggerated.”

KRE/AMB END GIBSON