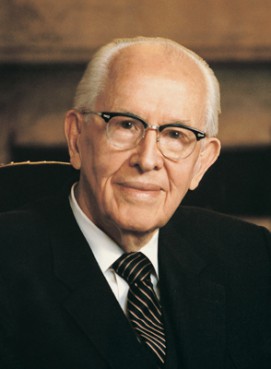

(RNS1-NOV18) Ezra Taft Benson, who served as president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints from 1985 to 1994, was an avowed anti-communist and a fan of the John Birch Society. For use with RNS-BENSON-FBI, transmitted Nov. 18, 2010. RNS photo courtesy LDS Church.

SALT LAKE CITY (RNS) The 1965 letter to FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover was packed with political dynamite, so Ezra Taft Benson marked it “personal-confidential.”

Benson, the only man to serve in a presidential cabinet and go on to lead a worldwide church, the Mormons, was attempting to convince Hoover that the John Birch Society was a clear-thinking anti-communist group. He wrote how it had convinced him that a mutual friend had been a tool of the worldwide communist conspiracy.

That friend was none other than former President Dwight D. Eisenhower, for whom Benson had served as secretary of agriculture from 1953 to 1961.

“In my study of the (communist) conspiracy, which I am sure is weak compared with your own, the consequences of Mr. Eisenhower’s actions in dealing with the communists have been tragic,” Benson wrote.

He argued to Hoover that Eisenhower had helped, more than hurt, the spread of communism, perhaps because it had been the expedient thing to do for an ambitious politician.

“What difference does it make if your house is burned down by an ignorant man, a person who wants to get warm fast, or an arsonist?” he wrote about the former president.

That and other letters in Benson’s thick FBI file, obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request, suggest that Benson was an early Tea Partier — one who would become an inspiration 50 years later for that modern movement.

Like the current Tea Partiers, Benson worried about threats to freedom and the Constitution. He feared that too many powerful officeholders — up to and including the U.S. president — were not standing up for the Constitution, and instead aided its enemies, out of ambition, expediency or other, more sinister motives.

The New Yorker magazine recently included Benson as one of the Tea Party’s ideological founding fathers, noting how Benson’s public writing and speeches are quoted and admired by Tea Party icon Glenn Beck, a Mormon convert.

Benson’s FBI files reveal a behind-the-scenes battle in which he sought to persuade the FBI not to condemn the John Birch Society, formed in 1958 by Robert Welch and named for a missionary-turned-soldier killed by Chinese communists after World War II.

The files also show that Hoover’s FBI twice spied on Benson — possibly for Eisenhower. Files also show that Hoover lied in later years to avoid Benson, seeking to distance himself from Benson’s support of the Birch Society.

Benson’s son, Reed, and Reed’s wife, May Hinckley Benson, said in a recent interview in their Provo home that the elder Benson’s hatred of communism was rooted in his experience as a new apostle sent by the LDS Church to oversee its relief efforts in Europe after World War II.

Benson later wrote that he watched half of the continent quickly fall to communism and lose the right to worship freely.

Soon after taking office in 1953, Benson sparked controversy by attacking government farm subsidies — worrying aloud that they were too socialistic, which upset farmers and members of Congress. In 1957-58 Benson created a similar storm for attacking dairy supports.

Benson’s FBI files indicate that agents poked around for whether Benson would resign; he stayed until Eisenhower left the White House in 1961.

Amid the spying by Hoover, the FBI director managed to leave the impression with Benson that they were friends and fellow fighters against communism. Files show they exchanged copies of books and speeches, notes and invitations.

“I realize that only in the next life will we fully appreciate all you have done to preserve freedom in this country,” Benson wrote Hoover in 1965. “I am most grateful for your exposure of the communist conspiracy and for the wonderful organization you have established in the FBI.”

But Benson was not so happy with others in the Eisenhower administration. Reed Benson said his father tried to persuade the State Department to rethink its support of Fidel Castro in Cuba, and didn’t like Eisenhower’s invitation to Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev to visit an agricultural experiment center near Washington in 1959.

Against such frustrations, Benson became involved with the John Birch Society after he left office. “The John Birch Society believed in less government, more individual responsibility and a better world,” Reed Benson said.

FBI logs note that Benson called the FBI to assess the bureau’s feelings toward the group, hoping to meet with Hoover “to confer with him about the menace of communism and the role of the Birch Society.”

Hoover’s aides repeatedly recommended keeping distance between Benson and the director.

In a 1965 letter to Hoover, Benson asked Hoover not to publicly criticize the society. “It is my conviction that this organization is the most effective non-church group in America against creeping socialism and godless communism,” Benson wrote.

Soon after, Hoover voiced his doubts about the society and its founder, prompting Benson to try to meet with Hoover to express his concerns. Files show that Hoover’s aides twice told Benson that he was unavailable for such a meeting. Later, Benson wrote the sensitive “personal-confidential” letter, outlining his conclusions about Eisenhower.

(BEGIN OPTIONAL TRIM)

Benson also sent a book by Welch titled “The Politician,” noting it was what led him to his conclusions about Eisenhower.

“How can a man (Eisenhower) who seems to be so strong for Christian principles and base American concepts be so effectively used as a tool to serve the communist conspiracy?,” Benson had written in the flyleaf of his own copy.

Benson also wrote of Eisenhower: “I presume I will never know in this life why he did some of the things he did which gave help to the (communist) conspiracy. It is not my divine prerogative to know the motives of men. It is easier, however, to judge the consequences of man’s actions.”

(END OPTIONAL TRIM)

Hoover sent back only a short note.

“It was indeed thoughtful of you to furnish me your views regarding the John Birch Society and its head,” Hoover wrote. He concluded simply, “I have taken note of your impressions.”

Later, Hoover largely cut contact with his friend, even as Benson kept sending him John Birch society materials. In 1971, after Benson requested yet another meeting, he was informed Hoover was “booked solidly” and unavailable.

Hoover died only a few months after that last requested meeting. Benson would live another 22 years, serving as president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints from 1985-1994 and watching the fall of communism in Eastern Europe. Benson died at age 94 in 1994.

(Lee Davidson writes for The Salt Lake Tribune.)