WASHINGTON (RNS) Though they are not in the majority in Israel, Orthodox Jews control the country's religious life. More liberal branches of Judaism have long argued that the Orthodox dominance is unfair, but made little headway in changing the status quo — until this year.

In May, after seven years of legal wrangling, Detroit-raised Rabbi Miri Gold, who immigrated to the Jewish state 35 years ago, won a case before the Israeli Supreme Court that will make her the first non-Orthodox rabbi to earn a state salary. The decision was hailed as an important first step by Reform, Conservative and other Jewish groups who want equity for all branches of Judaism.

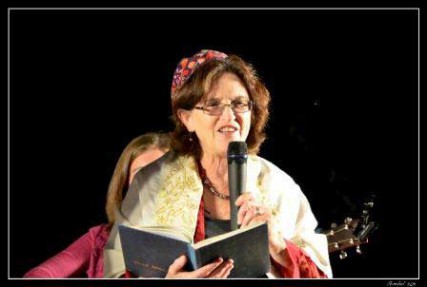

Rabbi Miri Gold, who this year won a landmark court case before the Supreme Court of Israel that will make her the first non-Orthodox rabbi on the state payroll. **Note: This photo is not available for download.

We caught up with Rabbi Gold on her October tour of the U.S., where she is speaking about the court decision, prospects for religious pluralism in Israel, and why she actually believes in the separation of church and state.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: Why is it that most Israelis don’t consider themselves Orthodox, yet the very Orthodox still control religious life?

A: Right after the court case was decided, this one guy really annoyed me because he told me right away that he’s secular but he believes the ultra-Orthodox have the “right way” about Judaism. You have a percentage of Israelis who are like that. I’d say more Israelis are indifferent.

Q: It’s like that saying, “The synagogue that I don’t go to should be Orthodox.” Why do so many Israelis feel that way?

A: Because that’s all they know. Israel is still pretty provincial. Those who get out of the country and come and study, or work, go back much more informed and more open. Maybe they even had a positive connection with a synagogue that’s not Orthodox.

My hope is that when Israeli kids come to work in American Jewish camps, whether Reform or Conservative, the camp will make the effort to say, “When you go back to Israel, you can connect with either movement, and find that it might speak to you.” A lot of times these people come back and they’re ambassadors in a way. Things soften up slowly but surely.

Q: What's next on the agenda for non-Orthodox rabbis in Israel?

A: On to bigger and better things. We want to legalize marriages that we perform and let our conversions be registered without people having to go to court. The struggle isn't over yet.

Q: Why is the struggle for religious pluralism important beyond Israel?

A: Pluralism has in its message that we have to be respectful of one another. And as somebody said to me recently, maybe if there was more unity in Israel about religious pluralism, it would be easier to solve some of the bigger political issues, even with the two-state solution. Because if you respect people around you, maybe you can better respect people who you don't feel the same familial connection to.

Q: Court decision aside, how have things changed since 1999, when you were ordained in Israel, a country where the idea of a female rabbi can still be very alien?

A: My children were young when I went to rabbinical school. They never told their friends that their mother was a rabbi, because they would have to explain it. I felt things had changed when, after the court decision was announced, my daughter put it on Facebook. This is the same daughter who, when she was in the Israeli army, never told anybody.

Q: That daughter was somewhat unusual, in that, as a girl growing up in Israel, she had a bat mitzvah, or Jewish coming of age ceremony. Growing up in the U.S. in the 1960s, did you have a bat mitzvah?

A: Growing up in a Conservative synagogue in Detroit, I did not have a bat mitzvah. When I graduated from college, I went back to the rabbi and said, “Now can I have a bat mitzvah?” No. I had my bat mitzvah celebration when I was 32, with a baby in my hands.

When my daughter was called to the Torah, kind of kicking and screaming, she said, “it's only the daughters of your American friends who have bat mitzvahs.” But thank goodness she went along with it.

Q: You fought to be the first non-Orthodox rabbi on the State of Israel’s payroll, yet you believe in the separation of church and state. How does that make sense?

A: I grew up in the U.S. You see in Israel how, because of politics, the rabbinate has this really firm grip. It would be healthier if it would be separated. On the other hand, I understand why it’s not.

Israel, after the state was declared, was trying to strengthen Jewish life. I think separation of church and state is going to happen, maybe when we hit the Messianic era. But as long as the state is giving money to one religious group, why not give it to the other?

KRE/AMB END MARKOE