WASHINGTON (RNS) She was a simple Jewish girl who became a mystical bride, whose love for her miraculous son embodied a message of love from God.

She was the new Eve, the woman offered paradise — eternal salvation — who made the right call by saying “yes” to God.

The Virgin Mary, possibly the most frequently imagined woman in all of Western art, takes center stage in a landmark Washington exhibition of more than 60 sculptures, portraits, prints and other works by acclaimed Renaissance and Baroque artists on loan from the Vatican and other leading museums and private collectors.

“Picturing Mary: Woman, Mother, Idea” opens Friday (Dec. 5) and runs through April 12 at the National Museum of Women in the Arts, just in time for Christmas and stretching past Easter.

The theme of the show is Mary’s symbolic power, expressed in the arts. She touches people’s hearts “not only in a religious dimension but in a human dimension,” a way of seeing the human experiences of love, devotion and suffering, said Marian scholar Monsignor Timothy Verdon. He’s a curator for the show, director of the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo in Florence and a co-author of the exhibit catalog.

Washington Post critic Philip Kennicott called the Christmastime crowd-magnet exhibit a bit too merry Mary, although “Mary isn’t entirely a feel-good icon.” His review concluded with a complaint that modern and controversial art works were omitted and that the show’s overall message falls narrowly within the Roman Catholic tradition.

A companion online exhibit, A Global Icon: Mary in Context, offers images from beyond Europe, in partnership with the Google Cultural Institute. The Museum is also offering an online highlights tour of the D.C. exhibit and there will be scholarly programs offered by The Catholic University.

Some highlights from the show and their descriptions from Verdon and the exhibit catalog:

Sandro Botticelli (Alessandro Filipepi), Madonna and Child (Madonna col Bambino), also called Madonna of the Book (Madonna del Libro), 1480–81; Tempera and oil on wood panel, 22 7/8 • 15 5/8 in.; Museo Poldi Pezzoli, Milan; inv. 443. Photo courtesy of National Museum of Women in the Arts

In this Botticelli image (above), the Christ child is centered between Mary and the book, a physical representation of an idea, said Verdon, that Christ was “God’s Word made flesh” to enter human history.

And Mary’s mournful look, like the tiny nails in Jesus’ fist and his bracelet ring of thorns, shows her awareness that her son “will suffer, as will we all.”

Elisabetta Sirani, Virgin and Child, 1663; Oil on canvas, 34 × 27 1/2 in.; National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, D.C., Gift of Wallace and Wilhelmina Holladay; Conservation funds generously provided by the Southern California State Committee of the National Museum of Women in the Arts. Photo courtesy of National Museum of Women in the Arts

Even in the knowing context of biblical history, when Mary learns early of her son’s fate, she’s still a young mother.

Sirani, one of four female artists in the exhibit, offers an image of the duo at play (above). It’s one of several that show them being playful, giggling, teasing, enjoying the delightful side of love, said Verdon.

Sofonisba Anguissola, Self-Portrait at the Easel, 1556; Oil on canvas, 26 × 22 3/8 in.; Muzeum-Zamek, Łańcut; inv. 916MT. Photo courtesy of National Museum of Women in the Arts

What does it mean to see Mary reflected in your own life?

Sofonisba Anguissola’s dignified, almost defiant self-portrait was made at a time when it was rare for a woman to have a career in the arts, much less to show herself in the status of someone who paints the Madonna and child.

It is as if the artist says to the viewer, “I can do this, too,” said Verdon.

Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, Madonna of the Goldfinch, ca. 1767–70; Oil on canvas, 24 13/16 × 19 13/16 in.; National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; Samuel H. Kress Collection; inv. 1943.4.40. Photo courtesy of National Museum of Women in the Arts

Tiepolo’s lush portrait of the decorously dressed Mary shifts the viewer away from the 14th-century portrayal of Mary as the queen of heaven to the 18th-century focus on the prince in her arms.

Federico Barocci, Rest on the Flight into Egypt (Il Riposo durante la Fuga in Egitto), also called Madonna of the Cherries (La Madonna delle Ciliegie), 1570–73; Oil on canvas, 52 3/8 × 43 1/4 in.; Vatican Museums, Vatican City; inv. 40377. Photo courtesy of National Museum of Women in the Arts

Several works in the exhibit portray the theme of Mary and her infant’s flight into Egypt. Above, in a “sunny and delightful scene” by Barocci, they are relaxed, enjoying an interlude by a stream beneath a cherry tree, said Verdon. Mary is shown as both a silken-dressed aristocrat and a simple country woman with a straw hat. And Christ is simply a happy child.

Showing Mary as a real woman, a real mother, portrays a “view of the earthly world and humankind as the most compelling manifestation of God’s love,” as the curators note in the exhibit.

Caravaggio (Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio), Rest on the Flight into Egypt (Il Riposo durante la Fuga in Egitto), 1594–96; Oil on canvas, 53 3/8 × 65 1/2 in.; Galleria Doria Pamphilj, Rome. The Caravaggio is on loan from the Trust Doria Pamphilj. Photo courtesy of National Museum of Women in the Arts

This early masterpiece by Caravaggio (above), “Rest on the Flight into Egypt,” draws on apocryphal “Infancy Gospel” versions that describe the Holy Family accompanied by angels on their journey.

The viewer first focuses on the dominant figures of a rustic Joseph who holds the music for an angel musician. But then the eyes rest on Mary and her sleeping child, “so delicate and sweet.”

And so telling. Sleep is often shown as a foreshadowing of death. Verdon marveled that Caravaggio, a violent and troubled artist, could reveal a believer’s soul in this work.

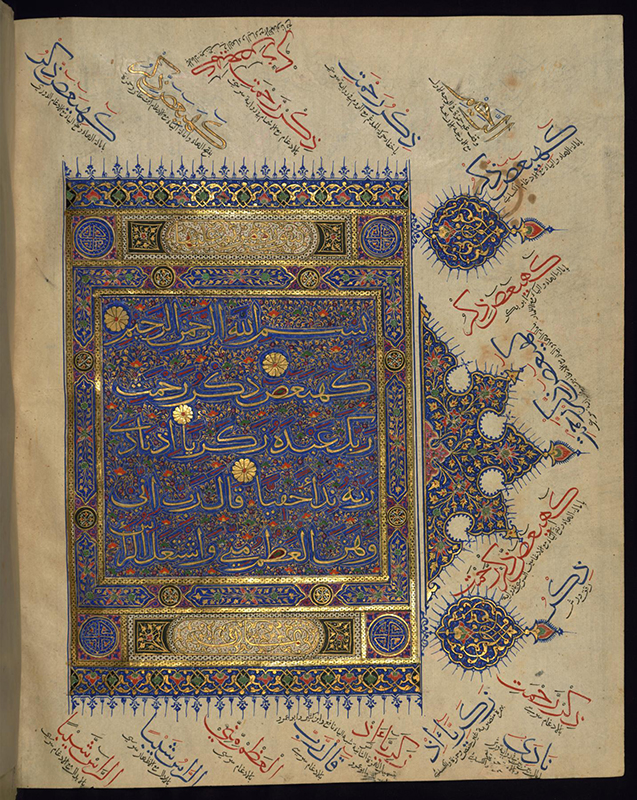

Below are three images from around the world — including one showing title pages of the Quran chapter named for Mary — that are part of the online companion exhibition.

This sculpture representing the Immaculate Conception reflects the cross-cultural importance of Mary. Its hands and face were carved from ivory in the Philippines and then shipped to the New World, where they were set into the wooden sculpture. Unknown artist, “Virgin of the Immaculate Conception,” 18th century; Philippines and Guatemala; Wood, ivory, pigment, gilding, gessoed cloth, and silver, 25 7/8 x 27 x 10 1/4 in.; Brooklyn Museum, Frank L. Babbott Fund; inv. 42.384. Photo courtesy of National Museum of Women in the Arts

Created in Ceylon, an island off the southeastern coast of India (now Sri Lanka), this piece represents a stoic Virgin that combines typical European attributes of the Immaculate Conception—crown and crescent moon—with the streamlined elegance and facial features of Indian sculpture. Unknown artist, “Virgin of the Immaculate Conception,” ca. 1690–1710; Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka); Ivory with gilt and polychromy, 10 1/8 in. high; Walters Art Museum; inv. 71.341. Photo courtesy of National Museum of Women in the Arts

This is the second of two title pages from the Surat Maryam, a chapter on the Virgin Mary found in the Qur’an. Mary is the only woman to have a chapter named after her. Unknown artist, “Chapter 19 of Qur’an (Surat Maryam),” 15th century; Northern India; Ink and pigments on thin laid paper, 15 3/4 x 12 3/16 in.; The Walters Art Museum; inv. W.563.274B. Photo courtesy of National Museum of Women in the Arts