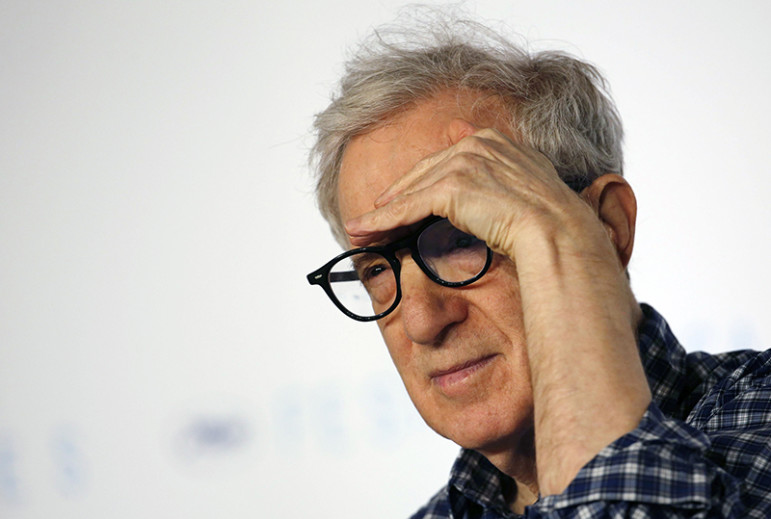

Director Woody Allen gestures as he attends a news conference for the film “Irrational Man” out of competition at the 68th Cannes Film Festival in Cannes, southern France, on May 15, 2015. Photo courtesy of REUTERS/Regis Duvignau

Woody Allen — film maker, author, playwright — turned eighty years old this week.

I have been a fan of Woody Allen’s work for more than half of my life (though not of his personal choices).

Question: has Woody Allen’s career been “good for the Jews?”

Yes, Woody Allen is Jewish — or, as he would put it, “Jewish — with an explanation.” Like many Jewish entertainers, he is utterly removed from the Jewish community and Judaism.

In Eric Lax’s biography of Woody Allen, we find this “confession:” “I was unmoved by the synagogue. I was not interested in the Seder, I was not interested in the Hebrew school, I was not interested in being Jewish. It just didn’t mean a thing to me. I was not ashamed of it nor was I proud of it. It was a nonfactor to me…”

A “nonfactor?” Really?

Consider the most notable Jewish moments in Woody Allen’s filmography.

- What’s Up, Tiger Lilly?” (1966). A Japanese spy movie, with dubbed-in dialogue. A search for an “egg salad recipe so good you could plotz [die].” A Japanese hero named Phil Moscowitz. A Japanese character, mortally wounded, calls for his rabbi.in 1966, many Jews wanted to appear gentile; this time, it’s others (i.e., Japanese) who appear Jewish.

- “Take The Money And Run” (1969) Serving a prison sentence for robbery, Virgil Starkwell submits to an experimental medical treatment. It has a curious side effect — he turns into a Hasidic rabbi.

- “Bananas” (1971). In this tale of central American revolution, the CIA is supposed to send in military reinforcements. Instead of the CIA, it winds up being the UJA — the United Jewish Appeal. In the midst of the fighting, Orthodox Jews walk around with puschkes (charity canisters).

- “Everything You Always Wanted To Know About Sex, But Were Afraid to Ask.” (1972). One vignette explains sexual perversion by featuring a rabbi whose fantasy is being bound and gagged while his wife is forced to eat pork at his feet. Many people have considered this scene to be over the top offensive.

- “Play it Again, Sam” (1972) . Wooing Diane Keaton, Woody shops for candles for a romantic dinner. Humphrey Bogart’s ghost appears and stops him from mistakenly buying yahrzeit (memorial) candles: “Don’t buy those candles, stupid — they’re for a Jewish holiday.”

- “Love And Death“. (1975). Young Woody Allen asks Father Nikolai about Jews. The Russian Orthodox priest shows him sketches of Jews: “The Russian Jew has horns; the German Jew has stripes.” A very subtle poke at Jewish inter-ethnic rivalry.

- “Annie Hall” (1977). One of the classic Jewish scenes in American cinema. Alvy Singer visits Annie’s family in Wisconsin. He imagines that Annie’s grandmother sees him as a Hasidic rabbi — a satiric reflection on how Jews imagine gentiles imagining Jews.

- “Manhattan“ (1979). Isaac (Woody Allen) declares his love to (the far too young), Mariel Hemingway:” You’re God’s answer to Job…”

- “Zelig“ (1983). Leonard Zelig is a human chameleon, taking on the identity of anyone who happens to be around him. It is a parable about assimilation — the Jew as compulsive imitator.

- “Crimes and Misdemeanors” (1989). The main character is named Judah; a rabbi is losing his sight, and there is a flashback scene at a seder. “Crimes and Misdemeanors” is considered one of the most “Jewish” films in contemporary cinema.

Woody Allen’s essays are even more Jewish.

In his collection Without Feathers, there is “Hassidic [sic] Tales, with a Guide to Their Interpretation by the Noted Scholar.” It is a satire on Hasidic stories, but it is an affectionate satire. It is clear that Woody has actually read those tales, perhaps in the version made famous by Martin Buber.

Or, “The Scrolls.” These are parodies on biblical tales, but again — loving parodies. Woody’s re-telling of the akedah (the binding of Isaac) has God castigating Abraham: “Some men will follow any order no matter how asinine as long as it comes from a resonant, well-modulated voice.” It is a great midrash.

Woody Allen’s nightclub routines are deeply Jewish. A Jewish couple, the Berkowitzes, dress up as a moose, and wind up, shot and mounted, on the wall of the restricted New York Athletic Club. A Jew successfully sells Israel Bonds to members of the KKK. A rabbi appears in a vodka ad.

Woody Allen is estranged from “official” Jewish life. But, here is the paradox: Allen fled from everything Jewish in his personal life, and yet keeps returning to Judaism as a topic for his humor.

Woody Allen’s work reflects a proud secular Jewish literary tradition. That tradition goes back to Kafka, Malamud, Bellow, and Philip Roth. His comic mishpoche (family) includes Lenny Bruce, Jerry Seinfeld, Larry David, Sarah Silverman, and Amy Schumer. It is a tradition of approach-avoidance.

On the one hand, there is the rejection of Judaism as religion. But there is the re-invention of Jewish identity as attitude — mostly of irony and iconoclasm.

The question is: how much longer will we have a Judaism of attitude — at the expense of a Judaism as religion? Will our children and grandchildren care enough to create even that?

Not if the next generation of Jews are Allenists — those for whom Judaism is a “nonfactor.”

Idea: a Woody Allen movie about the Pew report on Jewish identity?

Probably not going to happen.

Still I hope that Woody wouldn’t mind if I wish him — may you live to be 120.