WASHINGTON (RNS) Hoping to make the world safer, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum has published a guidebook on countering dangerous speech, authored by a young American who helped quell intertribal conflict in Kenya during its 2013 elections.

“Defusing Hate: A Strategic Communication Guide to Counteract Dangerous Speech,” doesn’t reveal exactly how to quell incendiary speech. The nature and context of speech that can lead to violence vary too widely across the globe for any particular prescription to make sense.

But the 160-page guide, a first-of-its-kind effort, gives local leaders ways to understand the environment that gives rise to this speech, and to come up with plans to defuse it before it inspires its audience to take up arms.

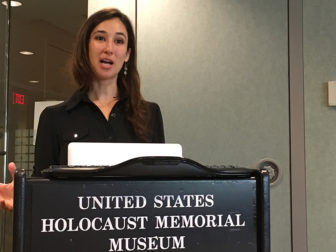

Rachel Hilary Brown, author of a new guidebook on combating speech that can lead to violence, speaks during its release on June 27 by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington. RNS photo by Lauren Markoe

“Unfortunately, I think this guide is more relevant than it was when we started this project,” said Rachel Hilary Brown, its author. She began work on it two years ago, as a fellow at the museum’s Simon-Skjodt Center for the Prevention of Genocide, which released the guidebook Monday (June 27).

The nonprofit Brown co-founded in Kenya when she was 22 — Sisi ni Amani, or “We Are Peace” in Swahili — organized a 2013 campaign that disseminated peace-affirming text messages to counter provocative rumors spread by mobile phones in the nation. In the 2007-2008 election cycle, more than 1,000 Kenyans died after allegations that the vote was rigged.

Sisi ni Amani’s approach has also worked in land disputes. The group wrote a text to armed men poised to fight: “Let us resolve all boundary issues peacefully, for only with peace can we find lasting solutions. Let us keep peace in Mulot.” The message gave pause to the would-be fighters in the region northeast of Nairobi, and they took their disagreement to a local pastor to mediate.

Brown and the Holocaust museum hope “Defusing Hate,” which is available at no cost online, will help local activists elsewhere design campaigns that will resonate with carefully targeted audiences. The book offers strategies for defining that audience, crafting a message, choosing the medium by which to spread it and avoiding common pitfalls — such as trying to debate purveyors of dangerous speech.

The guidebook advises: “frame a grievance as a socioeconomic issue rather than an ethnic or religious one.”

Annie Bird of the Department of State’s Bureau of Conflict and Stabilization Operations said that the guidebook has already been used to train foreign service officers and that it should be relied on as the department begins to spend new funds allocated to prevent atrocities.

“Now we have a robust guide to help us figure out how to design a program,” she said to Brown at the guidebook’s launch. “I would love to see us actually pilot some work using your guide in countries at risk.”

Professor Susan Benesch, who coined the term “dangerous speech.” Photo courtesy of American University

The guidebook draws on the work of American University Professor Susan Benesch, who coined the term “dangerous speech” to mean speech that increases the risk for violence for a group of people.

Brown also uses the term “dangerous speech” as opposed to “hate speech.” As Benesch has argued, hate speech is not always dangerous — a person yelling ethnic slurs within earshot of no one, for example, is guilty of hate speech but likely not dangerous speech.

Benesch says countering dangerous speech is a new field, and the work is hard. The emotions that underlie dangerous speech tend to be visceral, and once dangerous speech is disseminated, its damage is often done. The internet and social media make it easier to spread such speech, and the possibility of anonymity emboldens offenders.

So while effective examples of countering dangerous speech online are uncommon, they are notable, said Benesch, who is just finishing a two-year study of the phenomenon.

She gives the example of the response to a slew of racist tweets in 2014 denigrating the newly crowned Miss America, who was Indian-American and wrongly assumed to be Muslim and Arab. “More like #MissTerrorist” read one tweet. But Twitter users confronted the racist tweeters online, leading some of those who made the original comments to apologize, and delete what they had written.

Among the preliminary conclusions of Benesch’s study: Trying to eliminate dangerous speech is rarely the best strategy.

“Instead of trying to censor all of this speech, which would be difficult or impossible, we try to inoculate people against it, to make them less susceptible to it,” Benesch said.

But she also warns of the limits of her field.

“Counter speech can perhaps be a useful tool, but it is certainly not the solution all by itself,” she said.

“The way parents raise their kids has got to be number one.”