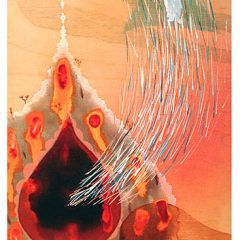

- Part of series “Primeras frutas” by Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia, 2007. Photo courtesy of Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia

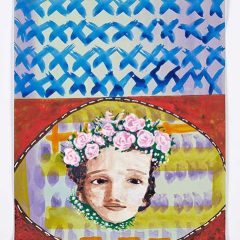

- “Novenario” by Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia, acrylic ink on paper, 2006. Photo courtesy of Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia

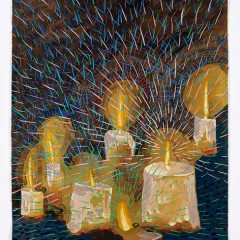

- “La Navidad” (nino dios) by Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia, acrylic and thread on paper, 2016. Photo courtesy of Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia

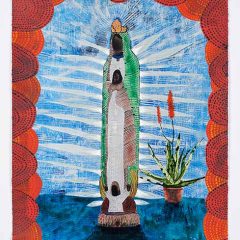

- “Reflexiones sobre la muerte” (Novenario) by Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia, acrylic and paper, 2016. Photo courtesy of Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia

- “Reflexiones sobre la muerte” (Bodegon con estatuilla), acrylic on paper, 2016. Photo courtesy of Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia

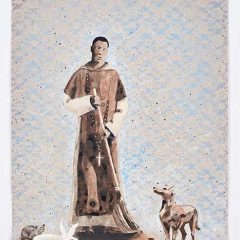

- “Reflexiones sobre la muerte” (San Martin de Porres), acrylic on paper, 2016. Photo courtesy of Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia

- “Kuntur Amaru” by Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia, found wood, 2017. Photo courtesy of Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia

- “Nuestra Senora Reina de Los Angeles” by Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia, found wood, 2016. Photo courtesy of Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia

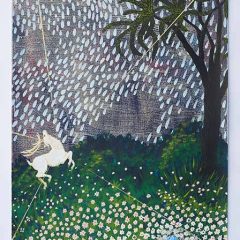

- “Pushing Daisies (Resurrection Painting)” by Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia, acrylic on paper, 2017. Photo courtesy of Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia

- “Esperanza de los justos (Hope of the just)” by Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia, acrylic on paper, 2017. Photo courtesy of Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia

- Installation, “God’s Eye,” by Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia, yarn. Photo courtesy of Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia

- “Untitled (4)” by Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia, sand and tar on linen over panel, 2017. Photo courtesy of Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia

- “Untitled (6)” by Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia, sand and tar on linen over panel, 2017. Photo courtesy of Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia

- “Untitled (7) by Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia, sand and tar on linen over panel, 2017. Photo courtesy of Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia

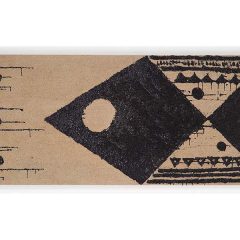

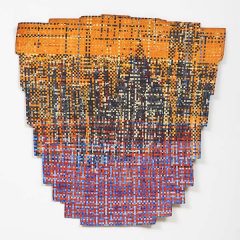

- Woven paper from “Vida, pasion y muerte” by Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia. Photo courtesy of Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia

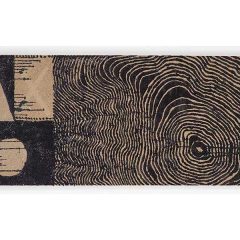

- Woven paper from “Vida, pasion y muerte” by Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia. Photo courtesy of Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia

- Coffin, from “Vida, pasion y muerte,” by Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia, acrylic, glass beads, metallic muslin, 2017. Photo courtesy of Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia

- “Vida, pasion y muerte” by Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia at CB1 Gallery, Los Angeles, 2017. Photo courtesy of Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia

LOS ANGELES (RNS) — Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia had a full scholarship to study engineering and was more than halfway to his degree when he took an art class.

It changed his life.

Today, Hurtado Segovia, 38, is a much-admired contemporary artist who lives, works and shows in this city, which has become ground zero for much of American contemporary art. He is fresh off a critically acclaimed solo show that one reviewer called “deftly crafted, quirky, spiritual, private and timeless.”

Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia, 38, is a contemporary artist who taps into his faith to create art that pushes back against conservative notions of Christianity. RNS photo by Kimberly Winston

He is also a Christian, something that frequently makes its way into his work in ways both open and veiled. And while the contemporary art world often dismisses religious subjects — especially if they’re not critical — faith is both a touchstone and wellspring for almost all of his abstract works in wood, fiber, paper, paint and even sand and tar.

For Hurtado Segovia, Christianity is not just a faith. It’s woven into his Mesoamerican identity, evident in his use of handicrafts such as embroidery and beads.

“I am convinced art is my vocation, my passion, my calling, a deep part of my being,” he said recently from the sunny living room of the second-floor apartment that is both the home he shares with his wife and two children and his studio. “My faith in Jesus filters how I understand the world and the art I make that goes out into the world is therefore a seamless entity as a practice.”

And the religious subject matter of his art has a purpose, one that may not endear Hurtado Segovia to either the contemporary art world or some of his fellow Christians: reclaiming from conservatives what it means to be a Christian and love God.

[ad number=“1”]

“For Lorenzo, Christian values are not what the media portrays as Christian values on the basis of — and I will use the word ‘evangelical’ Christianity, even though, to me, evangelical Christians is not what a lot of these people are,” said Clyde Beswick, the co-owner of CB1 Gallery, the downtown Los Angeles space that represents Hurtado Segovia.

“To me, Lorenzo is what Christians should be. He lives his faith, he cares about people, and I have never seen him break away from his position of what Christianity is to him, which is living out the love of God.”

Signed with an ‘X’

Hurtado Segovia was born and raised in the Colonia Azteca section of Juárez, Mexico, just across the border from El Paso. It was a collection of small, cinder block houses carved out of a hillside.

When he gives talks about his work, he includes slides of the things that influence his art — the Mexican Catholicism in which he was raised, the dangerous and athletic dances of the “voladores” and “matachines,” and bright knits, beadwork, floral embroidery and geometric weaving.

Most of the titles of his works are in Spanish and he signs them with an “X” — a nod to his beloved grandmother, who was illiterate and very religious.

Hurtado Segovia graduated from the University of California at Los Angeles with a degree in art, but it wasn’t until he pursued his master’s degree at Otis College of Art and Design that he began expressing his faith in his art. Even then, his professor and mentor, the contemporary artist Roy Dowell, sensed a restraint.

“Roy said, ‘Why, when you talk about your art you don’t acknowledge that? Are you embarrassed?'” Hurtado Segovia remembered.

He replied that he was worried his faith would not be taken seriously — that it would be seen as a lack of “critical thinking,” he said.

[ad number=“2”]

But Dowell — who is an atheist — challenged his student not to “‘close up the doors before you even knock at them.’

“That really started me going,” Hurtado Segovia said.

Dowell, who founded Otis’ fine arts master’s program, said Hurtado Segovia’s faith is a foundational part of what makes his art worth viewing.

“He has a confidence in both his ethnic background and his belief system that offers him, as an artist, a great deal,” he said. “I think he was afraid to use those things in fear that they would typecast him as a religious artist or an ethnic artist. But these are the things that you know, that you have at hand, so you use them.”

Prayers and papers

Sometimes, the religious subject matter of Hurtado Segovia’s work is upfront.

From the “Pelgarias” series, “Por paciencia.” Photo courtesy of Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia

Between 2006 and 2015, he did a series of works on paper called “Plegarias” (“Prayers”), abstract renderings of dashes and vague floral shapes, dots, lines and rectangles. Only the titles reveal their intent — “Por paciencia” (“For Patience”), “Por esperanza” (“For Hope”) and “Por mis hijos” (“For My Children”).

“One of the challenges I have is to speak to Christians and to non-Christians in an accessible language,” Hurtado Segovia said, rearranging works on the dining room table that serves as his studio. He has tattoos of question marks on his left hand — to represent his questioning of the status quo — and exclamation marks on his right — a nod to his many blessings.

“I cannot be speaking in tongues,” he concluded.

Then there are works where his faith is coded in traditional Christian iconography that the viewer may or may not recognize. In “Papel tejido” (“Woven Paper”), a series of woven paper works, groups of three appear throughout — a symbol of the Holy Trinity, as well as shapes that could be crosses, steeples or winged doves, a symbol of the Holy Spirit. Several are woven into a form that resembles the outline of a papal robe or a shroud.

From the “Papel tejido” series. Some of Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia’s works are not overtly Christian, but embody images or shapes evocative of Christianity. Here, his woven paper is made in the shape of a papal garment. Photo courtesy of Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia

For “Mis Papeles” (“My Papers”), his 2015 solo show at East L.A.’s Vincent Price Art Museum, Segovia painted both sides of his paper with specific images or designs, sliced it into quarter-inch strips, and wove it by hand into works that measured up to 14 feet in length — no glue involved.

One of these works, the massive “Él derrama lluvia sobre la tierra y envía agua sobre los campos” (“He provides rain for the earth and sends water on the countryside”) is inspired byJob 5:10.

On the front, there is a flowery field and blue sky with an overarching rainbow, God’s promise to Noah that he would not send a second flood.

But the reverse side — separated from the Eden-like front by one-eighth of an inch — is a fire-colored vision of hell with dark figures that could be souls in torment.

One of Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia’s “papeles” — woven paper. On the front, an image of Eden, complete with the rainbow God sent Noah; on the back, an image of hell. Photo courtesy of CB1Gallery

This traditional Christian idea of an equally imminent heaven and hell is his response to a more conservative Christianity that views only the saved as eligible to enter the pearly gates.

“God’s grace is in the sunrise and the ocean,” Hurtado Segovia explained. “Those things are not just for believers; they are for everyone, like God’s mercy is extended beyond the conservative Christian view of his grace. It is for everybody.”

Karen Rapp, former director of the Vincent Price Art Museum, encountered one of Hurtado Segovia’s papeles in another show and wrote down his name, knowing she had to see more. His work, she said, shows the work of “a virtuosic hand.”

“When Lorenzo is choosing his (religious) symbols, he is choosing them from a place of authenticity,” she said. “I find it so welcoming — not threatening in any way. It does not announce itself as Christian art, as it might have.”

[ad number=“3”]

Rapp will include Hurtado Segovia’s “Cetros” (“Scepters”), a series of tall poles woven with bright fiber and inspired by the voladores in a January show at Loyola Marymount University’s Laband Gallery, where she is now director and curator.

“He really is able to incorporate his beliefs and convey them in a very warm and very welcoming manner and it is my conjecture that there is a certain respect that I think people have for his faith in his work.”

‘Segundo’ life

In other works, Hurtado Segovia’s faith is felt not in images, but in intent. He has repeatedly explored the Christian idea of salvation, renewal and rebirth in his materials, though not always in the images proper.

“Luchadora” from the “Segundas” series. Photo courtesy of Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia

In a project called “Segundas” (“Seconds”), Hurtado Segovia prowled L.A.-area thrift shops for handmade art, paying $5 or $10 for pieces that caught his eye. In his studio — again, the dining room table — he created his own piece inspired by the thrift-store art and put it in the frame. He took the finished painting — signed only with an “X” — back to the thrift store where it sold again for a pittance.

When the Los Angeles Times discovered his project, Hurtado Segovia said it was intended as a critique of the bloated prices of contemporary art, but it was also a sly commentary on the Christian idea that everyone — or, everything — can be redeemed.

“A segunda is a metaphor, in a sense, for a second life,” he told the Times.

He played with this metaphor again in a series of sculptures featured in his most recent solo show, “Vida, pasion y muerte” (“Life, Passion and Death”) at CB1.

The works, made from wood he scavenged from municipal tree crews, were fashioned into Madonnas, saints, totems, doves and condors — sacred to the Incan and Quechua peoples — with highly polished finishes and inlaid, stylized crosses.

For his solo show “Vida, pasion y muerte,” Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia used found wood to create images of Madonnas, doves and totems. In the background are his sand and tar works made with tar from the La Brea tar pits. Photo courtesy of Lorenzo Hurtado Segovia

“The Madonna is obviously Christian, but if you look at the entire body of work there were other things going on in there,” said Beswick, CB1’s co-owner. “They were really about what happened to Native Americans as a result of the Christianization of the New World with the boat-like image of Columbus and totem pieces that were very Pacific Northwestern.”

Then there is the theme of handicrafts, which have found their way into Hurtado Segovia’s works since his student days. Paper surfaces are interrupted with sections of embroidery, yarn erupts into square mandalas, and beads arranged in swags form frames.

Much of this craft he learned from his grandmother and mother and he sees it as a way of honoring their faith as well as his — he is now a member of a Protestant church.

“Taking something humble and exalting it — that is a model for understanding God’s mercy,” he said.

Dowell attended Hurtado Segovia’s latest show and was impressed.

“I think Lorenzo is starting to see that the things that he was maybe nervous about when he was a student have not in fact worked against him; they have worked for him,” Dowell said. “He is not pushing it, there is no arrogance there, he is quite sincere about what he is doing. You cannot deny that the viewer sees it. They may not recognize it as Christian, but they see it and they believe it.

“And that is the most important thing an artist can do — is get the viewer to believe what they are seeing.”