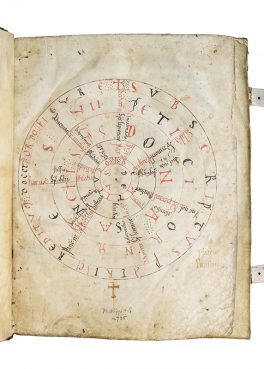

A Latin to English translation of the Liesborn Gospel Prayer Wheel. Photo courtesy of Les Enluminures Ltd.

“Langdon examined the thick vellum sheet. Written in ornate penmanship was another four-line verse.”

—Dan Brown, “The Da Vinci Code”

(RNS) — Call it my Da Vinci Code moment.

Three Aprils ago I found myself in a small gallery on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. I had been invited to report on a large sacred book from a medieval German monastery for which its owner was asking millions of dollars. I was having trouble finding a compelling angle, when the owner casually asked whether I had seen “the prayer wheel.” She drew my attention to a diagram on what had once been the book’s blank front page, added by an unknown party some 200 years post-publication.

The original Liesborn Gospel Prayer Wheel in Latin. Photo courtesy of Les Enluminures Ltd.

Like the symbologist Robert Langdon in Dan Brown’s 2003 novel, I examined the thick vellum, or cured calfskin sheet, annotated in an ornate script. The diagram was like nothing I’d seen before. It was a wheel composed of four concentric bands. Running inside each band was a text in Latin. But each of the texts was divided into seven parts, aligned with one another so the wheel also had seven spokes, or paths. One path was made up of all the Part Ones, another of all the Part Twos, etc. The paths ran from the wheel’s perimeter to its center, and where they met was inscribed the word “DEUS,” or “God.” Finally, there was a legend, one that seemed to come out of a fairy tale: “THE ORDER OF THE DIAGRAM WRITTEN HERE TEACHES THE WAY HOME.”

I was captivated. What wisdom did the diagram have to impart? How was it used? Did it have anything to offer us in the 21st century? These questions drew me and two friends tumbling into a world of faith and geometry, meditation and ancient infographics, where we spent, on and off, three years.

In my decades as a journalist I’ve read a lot of unusual documents, but never anything like this one, looking like a holy version of the Marauder’s Map from the “Harry Potter” series. The owner told me that the texts (all of which were familiar to medieval readers) were the Lord’s Prayer; the Beatitudes from Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount; a set of Christian attributes called the Gifts of the Holy Spirit, and a seven-part spiritual life of Christ. The point of the prayer wheel was to create monastic meditations and prayer along the paths, which recombined the texts into fresh new sequences — new roads “home” to God.

I felt an obscure thrill. The figure had an energy to it. It was very old, and yet it also felt very new; the sort of thing for which there might be an app. A lightly practicing Jew, I enlisted as partners my two friends — both believers who have written about their faith — to research it with me and consider the possibility that it might be of use to a modern Christian readership.

[ad number=“1”]

We discovered that between the 11th and 16th centuries there were probably hundreds, if not thousands, of such wheels distributed around Europe. But only 60 or so have survived, known only to a handful of academics and curators. We ran across copies of some of the later versions: They were much more involved, with up to 12 seven-part texts. Ours, from the 11th century, was early, a fairly pristine expression of the concept.

No smoking codex

But what, exactly, was the concept?

Since there was no smoking codex — nobody ever wrote “I created the prayer wheel” or even “My abbot drew me a prayer wheel because I needed to …” — we could not research it as a finished product: We had to reverse-engineer it, figuring out the histories of its essential characteristics.

Medieval people were fascinated by geometric and pictorial forms of presenting information that we would now call infographics. The figures featured squares, triangles and images of trees. We still talk about family trees. Other designs were specific to the era. A verse from the Bible’s Book of Proverbs, “Wisdom has set up her house; she has hewn it out of seven pillars,” inspired charts with seven supporting ideas holding up a desired conclusion.

[ad number=“2”]

The most popular shape, however, was the wheel. Symbolically, wheels have long fascinated humans as symbols of completion and perfection. Graphically, they were particularly useful for comparisons.

And this is where geometric display intersected with the wheel’s theological concerns. “Using Scripture to interpret Scripture,” as people still say today, is a practice as old as pre-Christian Judaism. Normally it involved reading one biblical passage in light of another, and later, dividing the two passages into seven parts apiece and comparing the parts for additional insight. The great thinker Augustine of Hippo extended that to three passages: The Lord’s Prayer, the Beatitudes and the Seven Gifts. A Benedictine monk named Radbertus added a fourth in the ninth century.

Let your fingers do the walking

And then, sometime in the 11th century, an unknown monk took the resulting horizontal grid of comparisons and pulled the ends of it around until they met to form a circle, placing “GOD” at the newly-formed center.

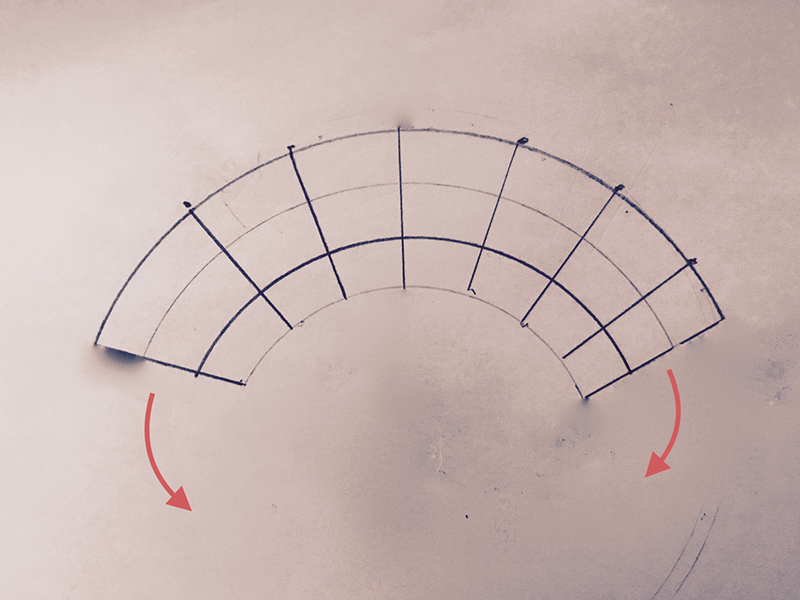

A continuous columnar table. Image courtesy of David Van Biema

Technically, this is called a “continuous columnar table.” Devotionally, it changed everything. What had been a static comparison for scholars was turned into a dynamic, interactive landscape, with paths to follow, and a clear goal for them to reach. One could project oneself into it. It was almost a board game: But the density of Christian concepts in the four base texts guaranteed that it was some of the most serious “fun” ever had. While the monks’ fingers walked, their souls followed, wondering at, and filling in the spaces between, the “stepping stones” with other Scriptures and with prayer.

Most likely monks and nuns used the wheel and its paths as a form of meditation, in a practice related to one called “lectio divina,” which involves the mental “chewing over” of very small scriptural passages. The diagram could have also been used as a memory trellis for other verses: medievals regarded memorization, too, as a form of devotion.

Prompting prayer

And we were off. While I continued to work on the wheel’s history and mechanics, my partners prayed it, and eventually developed a 49-day sample devotional path around it. You can see it in action at our Facebook page. The book that resulted also includes applications of the wheel for occasions (mourning, thanks, etc); a primer on praying for others with it, and illustrations of the way it dovetails with stories from the Bible.

[ad number=“3”]

Nowadays not so many believers meditate: But prompts for prayer are always welcome. Medieval tools like prayer at fixed hours of the day, labyrinths and lectio have all seen modern revivals. It’s too early to assume that the prayer wheel will join them, resuming a role something like the one it last performed centuries ago.

But what I can say is that walking into that showroom three years ago has already been an experience of discovery far richer than I could have imagined. It’s as close as I’ll ever get to an experience of the kind fictionalized in “The Da Vinci Code.” And unlike Brown’s novelistic puzzles, the wheel not only has a fascinating past, but the possibility of a spiritually meaningful future.

(David Van Biema, Time magazine’s former religion writer, is co-author with Patton Dodd and Jana Riess of “The Prayer Wheel: A Daily Guide to Renewing Your Faith with a Rediscovered Spiritual Practice.” The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

My real-life Da Vinci Code moment

Three years ago I discovered a strange diagram written into an ancient monastic book. (Commentary)

A Latin to English translation of the Liesborn Gospel Prayer Wheel. Photo courtesy of Les Enluminures Ltd.

“Langdon examined the thick vellum sheet. Written in ornate penmanship was another four-line verse.”

—Dan Brown, “The Da Vinci Code”

(RNS) — Call it my Da Vinci Code moment.

Three Aprils ago I found myself in a small gallery on Manhattan’s Upper East Side. I had been invited to report on a large sacred book from a medieval German monastery for which its owner was asking millions of dollars. I was having trouble finding a compelling angle, when the owner casually asked whether I had seen “the prayer wheel.” She drew my attention to a diagram on what had once been the book’s blank front page, added by an unknown party some 200 years post-publication.

The original Liesborn Gospel Prayer Wheel in Latin. Photo courtesy of Les Enluminures Ltd.

Like the symbologist Robert Langdon in Dan Brown’s 2003 novel, I examined the thick vellum, or cured calfskin sheet, annotated in an ornate script. The diagram was like nothing I’d seen before. It was a wheel composed of four concentric bands. Running inside each band was a text in Latin. But each of the texts was divided into seven parts, aligned with one another so the wheel also had seven spokes, or paths. One path was made up of all the Part Ones, another of all the Part Twos, etc. The paths ran from the wheel’s perimeter to its center, and where they met was inscribed the word “DEUS,” or “God.” Finally, there was a legend, one that seemed to come out of a fairy tale: “THE ORDER OF THE DIAGRAM WRITTEN HERE TEACHES THE WAY HOME.”

I was captivated. What wisdom did the diagram have to impart? How was it used? Did it have anything to offer us in the 21st century? These questions drew me and two friends tumbling into a world of faith and geometry, meditation and ancient infographics, where we spent, on and off, three years.

In my decades as a journalist I’ve read a lot of unusual documents, but never anything like this one, looking like a holy version of the Marauder’s Map from the “Harry Potter” series. The owner told me that the texts (all of which were familiar to medieval readers) were the Lord’s Prayer; the Beatitudes from Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount; a set of Christian attributes called the Gifts of the Holy Spirit, and a seven-part spiritual life of Christ. The point of the prayer wheel was to create monastic meditations and prayer along the paths, which recombined the texts into fresh new sequences — new roads “home” to God.

I felt an obscure thrill. The figure had an energy to it. It was very old, and yet it also felt very new; the sort of thing for which there might be an app. A lightly practicing Jew, I enlisted as partners my two friends — both believers who have written about their faith — to research it with me and consider the possibility that it might be of use to a modern Christian readership.

[ad number=“1”]

We discovered that between the 11th and 16th centuries there were probably hundreds, if not thousands, of such wheels distributed around Europe. But only 60 or so have survived, known only to a handful of academics and curators. We ran across copies of some of the later versions: They were much more involved, with up to 12 seven-part texts. Ours, from the 11th century, was early, a fairly pristine expression of the concept.

No smoking codex

But what, exactly, was the concept?

Since there was no smoking codex — nobody ever wrote “I created the prayer wheel” or even “My abbot drew me a prayer wheel because I needed to …” — we could not research it as a finished product: We had to reverse-engineer it, figuring out the histories of its essential characteristics.

Medieval people were fascinated by geometric and pictorial forms of presenting information that we would now call infographics. The figures featured squares, triangles and images of trees. We still talk about family trees. Other designs were specific to the era. A verse from the Bible’s Book of Proverbs, “Wisdom has set up her house; she has hewn it out of seven pillars,” inspired charts with seven supporting ideas holding up a desired conclusion.

[ad number=“2”]

The most popular shape, however, was the wheel. Symbolically, wheels have long fascinated humans as symbols of completion and perfection. Graphically, they were particularly useful for comparisons.

And this is where geometric display intersected with the wheel’s theological concerns. “Using Scripture to interpret Scripture,” as people still say today, is a practice as old as pre-Christian Judaism. Normally it involved reading one biblical passage in light of another, and later, dividing the two passages into seven parts apiece and comparing the parts for additional insight. The great thinker Augustine of Hippo extended that to three passages: The Lord’s Prayer, the Beatitudes and the Seven Gifts. A Benedictine monk named Radbertus added a fourth in the ninth century.

Let your fingers do the walking

And then, sometime in the 11th century, an unknown monk took the resulting horizontal grid of comparisons and pulled the ends of it around until they met to form a circle, placing “GOD” at the newly-formed center.

A continuous columnar table. Image courtesy of David Van Biema

Technically, this is called a “continuous columnar table.” Devotionally, it changed everything. What had been a static comparison for scholars was turned into a dynamic, interactive landscape, with paths to follow, and a clear goal for them to reach. One could project oneself into it. It was almost a board game: But the density of Christian concepts in the four base texts guaranteed that it was some of the most serious “fun” ever had. While the monks’ fingers walked, their souls followed, wondering at, and filling in the spaces between, the “stepping stones” with other Scriptures and with prayer.

Most likely monks and nuns used the wheel and its paths as a form of meditation, in a practice related to one called “lectio divina,” which involves the mental “chewing over” of very small scriptural passages. The diagram could have also been used as a memory trellis for other verses: medievals regarded memorization, too, as a form of devotion.

Prompting prayer

And we were off. While I continued to work on the wheel’s history and mechanics, my partners prayed it, and eventually developed a 49-day sample devotional path around it. You can see it in action at our Facebook page. The book that resulted also includes applications of the wheel for occasions (mourning, thanks, etc); a primer on praying for others with it, and illustrations of the way it dovetails with stories from the Bible.

[ad number=“3”]

Nowadays not so many believers meditate: But prompts for prayer are always welcome. Medieval tools like prayer at fixed hours of the day, labyrinths and lectio have all seen modern revivals. It’s too early to assume that the prayer wheel will join them, resuming a role something like the one it last performed centuries ago.

But what I can say is that walking into that showroom three years ago has already been an experience of discovery far richer than I could have imagined. It’s as close as I’ll ever get to an experience of the kind fictionalized in “The Da Vinci Code.” And unlike Brown’s novelistic puzzles, the wheel not only has a fascinating past, but the possibility of a spiritually meaningful future.

(David Van Biema, Time magazine’s former religion writer, is co-author with Patton Dodd and Jana Riess of “The Prayer Wheel: A Daily Guide to Renewing Your Faith with a Rediscovered Spiritual Practice.” The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

Donate to Support Independent Journalism!